Less Competition in Elections Breeds Hyperpartisanship

The Number of Competitive House Seats Has Dramatically Declined

If you talk to anyone who works with Congress for a living, more like than not, they will express frustration about how difficult it is to get anything done because of the hyperpartisanship that has overtaken the Legislative Branch. Politics is downstream from culture, so Members of Congress are largely reacting to a sentiment already there. That said, the quest for political power in the House is most evident in the district maps that are produced in the states.

Technically, 27 state legislatures control the redistricting process for House districts. Six states—Alaska, Delaware, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming—have only one House seat, so whatever process those states may or may not have doesn’t matter. The others use some form of commission, including independent commissions. However, only eight states have an independent commission. Even in states with a commission, the state legislature may have a say at some point in the process. I realize that there are a lot of details that I’m leaving out. For example, some states handle the commission process differently than others.

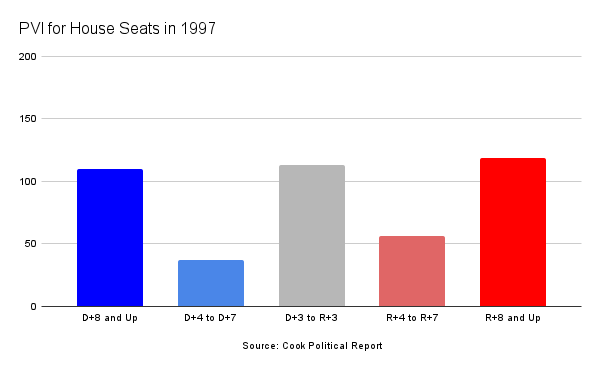

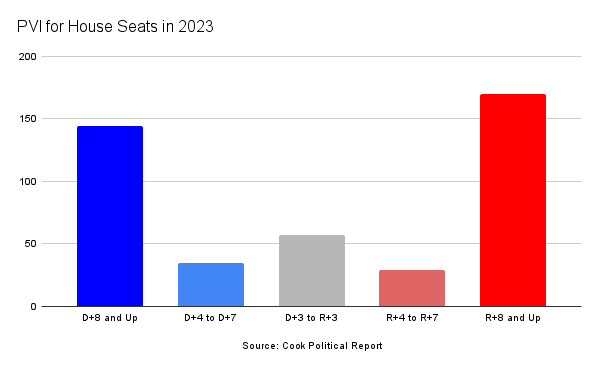

Recently, in preparation for a speaking engagement on political reform, I looked at the “partisan voter index” of the 435 districts that make up the House. As the Cook Political Report, which, I believe, coined the term, the partisan voter index (PVI) “measures how each district performs at the presidential level compared to the nation as a whole.” The number of competitive seats has widely changed.

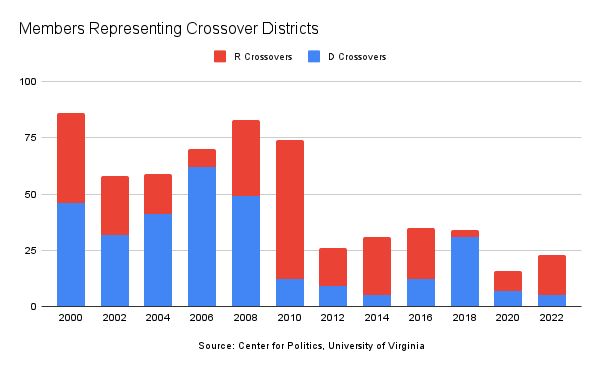

In 1997, there were 113 House seats with a PVI of D+3 to R+3. Today, there are 57. By my count, there were 72 “crossover districts,” meaning that the member who held these seats came from a different party than the presidential candidate who won the district. Today, there are 21.

Here’s a look at the PVIs in 1997.

Here’s what the PVIs look like today.

I have crossover district data going back to 2000. I had to pull the 1997 numbers from elsewhere, but you can see that the high-end came in 2000 with 86 crossover district members.

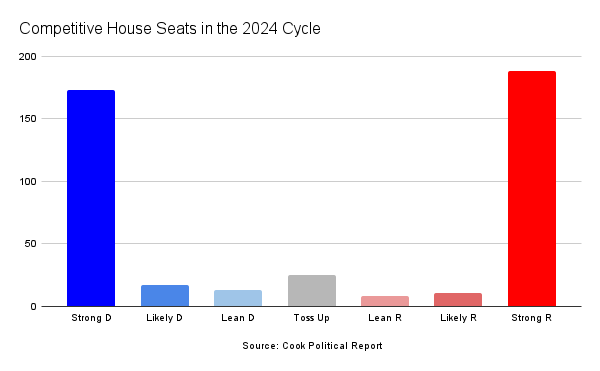

Now, let’s look at the competitive seats in the 2024 cycle. There are, by my estimation, 361 seats that are not competitive at all. By this I mean that the PVI is so tilted that one party can’t compete. I’m referring to seats with a PVI of D+8 and up and R+8 and up. That’s 83 percent of House seats. In 1997, 74 percent of House seats were in this category.

There are 28 that may be competitive. These are D+4 to D+7 and R+4 to R+7. In 1997, we were looking at 93 seats. There are 46 that are very competitive, which are seats that are D+3 to R+3. Again, in 1997, it was 113 seats.

Some may push back on this being something that’s driving hyperpartisanship in Congress. When the fringes of both parties are given more political power, it will necessarily drive the agendas of the parties further toward the extremes. I think that’s playing out in Congress right now, and we see it more often than we don’t. As I mentioned, politics is downstream of culture, so there’s more going on. I’m definitely not saying otherwise. It’s obvious that our politics incredibly problematic today, and there are far too many who thrive on influence and capitalize on divisiveness to line their pockets.

My theory is that moderation breeds moderation. A Republican-controlled Congress passed the first of four balanced budgets in 1997 and passed a capital gains tax cut, both of which were bipartisan and both of which were signed into law by President Bill Clinton. You may say, “Well, Pye, Republicans impeached Clinton at the end of that Congress.” Yes, they did, and voters responded at the ballot box reducing the Republican majority from 227 seats to 223 seats. The poor showing in the 1998 midterms also forced Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-GA) to resign.

But in today’s political climate, when which party controls 83 percent of House seats is essentially decided long before voters cast their ballots, the margins of the parties have much more sway and influence on what happens in the House. When so few seats determine the balance of power, the fringe becomes the kingmaker, and someone like Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) is completely beholden to those members.

How do we change this? Honestly, there’s no silver bullet. Arizona has an independent commission that has put three seats in very competitive range (D+3 to R+3) and another that could be competitive. That’s almost half the delegation. Two seats are above D+8 and three are above R+8.

Virginia has given us some competitive districts through its quirky process. The Virginia Redistricting Commission is responsible for drawing the maps. However, as state law states, the Supreme Court of Virginia steps in when the commission doesn’t do its job or the legislature doesn’t approve the maps. The Supreme Court of Virginia drew the maps for the 2022 cycle. There are two seats that are very competitive, three more that could be competitive, and six that aren’t at all competitive.

Hard partisans don’t like commissions, particularly Republicans, based on my experience. Republicans will also claim that any attempt to push through an independent commission at the federal level is unconstitutional. Eh, I don’t buy that. After all, the Constitution states, “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.” (Emphasis added.)

I’m not endorsing the idea of commissions, by the way. I do think it’s an interesting concept. I have an open mind about it, more than I ever have, because the way things are working now is just not tenable.