Social Security and Medicare Represent More Than $75 Trillion in Unfunded Obligations

New Trustees Reports Give an Updated Outlook for Social Security and Medicare

The Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Trust Fund is expected to run dry in 2033 while the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund is projected to run out of money in 2036. The looming actuarial problems that both trust funds face highlight the necessity and urgency of modernizing the two programs. Finding Members of Congress who agree—or are at least willing to tackle this task—is a difficult task.

Recently, a friend overheard someone say something like, “When are Republicans going to get over their love of the military so we can have some real spending reform?” I don’t disagree with the general sentiment here. Some Republicans would rather raise taxes than cut defense spending. But Republicans aren’t a monolith on defense spending or foreign policy.

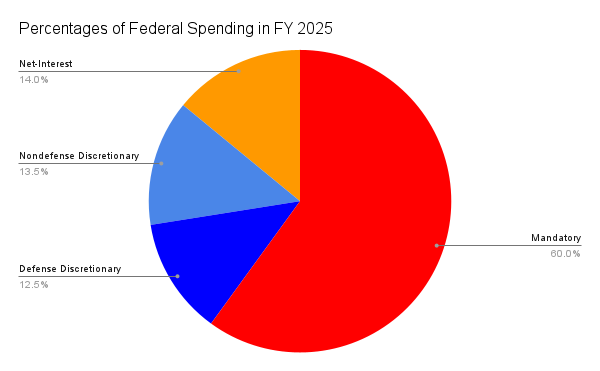

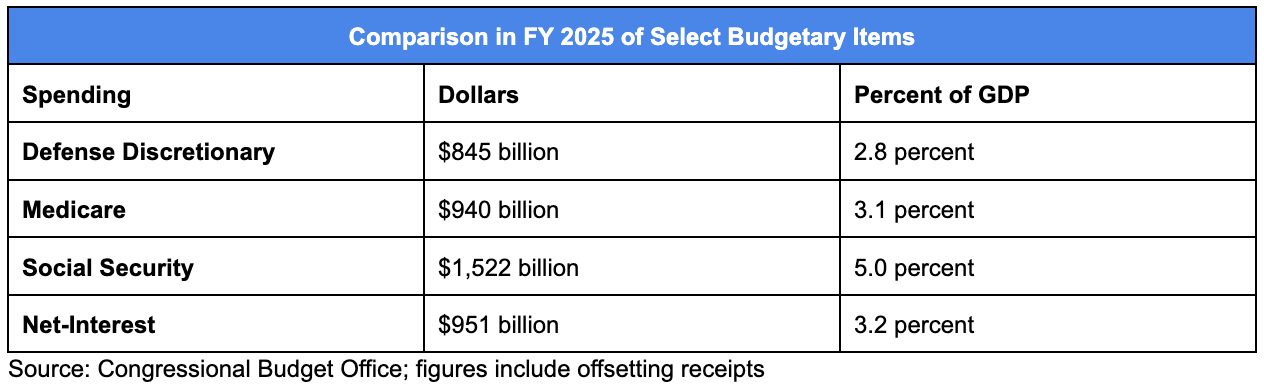

Still, when my friend told me about this comment, it set me off on a profanity-laced tirade because military spending—what we call defense or security outlays—is a relatively small part of all federal spending. It was 12.8 percent of all federal spending in FY 2024, and it’s projected to be 12.5 percent in FY 2025. Defense spending is currently expected to decline as a share of all federal over the budget window, falling to 10.4 percent in FY 2034. Of course, a future Congress could change that trajectory. This also doesn’t speak to the ancillary impacts on federal spending in the form of veterans’ benefits and military retirement, both of which amount to $279 billion in FY 2025, including offsetting receipts for military retirement.

Congress could cut reform defense spending—which is to say, get rid of expenditures that aren’t needed or otherwise get rid of waste—and it wouldn’t reduce the deficit by much. In 2016, for example, the Washington Post reported that reducing administrative waste in the Pentagon would save $125 billion over five years. That’s not nothing, and reducing this waste should be pursued, but it’s a drop in the bucket. There are other examples of waste that this story doesn’t capture, but you get the idea.

This is precisely why the focus on discretionary spending—including defense—really misses the mark. Frankly, it’s exceedingly dumb that some Members of Congress have focused only on discretionary spending as the means to federal reduce spending. Congress could cut defense and nondefense discretionary spending by 20 percent and 30 percent and still run a $1.33 trillion budget deficit in FY 2025.

What’s driving federal spending and, thus, budget deficits are three budgetary items: Medicare, Social Security, and net-interest payments on the federal debt. And, by the way, each of these exceeds defense spending. Which brings us back to the trustees’ reports.

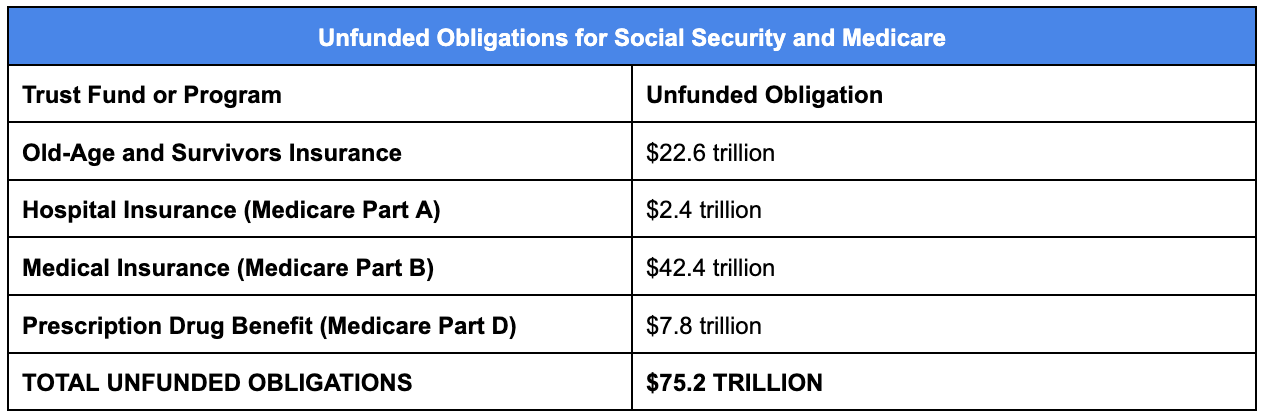

We’ll begin with Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI). The report states, “[T]he reserves of the OASI Trust Fund are projected to become depleted during 2033 under the intermediate assumptions.” This is the same year as projected in last year’s report. If the Disability Insurance reserves are included both trust funds will be depleted in 2035. The “good news,” if there is any, is that the combined depletion date is a year later than in last year’s report. If Congress does nothing, there would be an immediate 21 percent cut in scheduled OASI benefits. Overall, the unfunded obligation for OASI is $22.6 trillion through 2098.

The picture for the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund is a little rosier than last year. Again, I’ll caveat this “good news” as not really good since we’re talking about delaying the inevitable by five years compared to last year’s report. The reason for the change is, as the report states, “both the number of covered workers and average wages are projected to be higher” and “a policy change to exclude medical education expenses associated with Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollees from the fee-for-service per capita costs used in the development of MA spending.”

Like OASI, the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund would be able to cover only 89 percent of scheduled benefits in 2036 unless the program is modernized, or Congress bails it out. Still, it’s worth noting that the unfunded obligation for the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund declined from $4.4 trillion to $2.4 trillion. However, other Medicare programs—Medical Insurance (Part B) and the Prescription Drug Benefit (Part D)—don’t have dedicated revenue sources, and premiums don’t cover the cost. These costs are paid by general fund transfers. The unfunded obligation for Part B and Part D is $42.4 trillion and $7.8 trillion.

There are no easy answers to address these serious fiscal problems, but we should all prefer that Congress tackle these problems sooner rather than later. The Fiscal Commission Act, H.R. 5779, is one avenue to begin to address these questions. Unfortunately, resistance from some conservative groups who dare complain about spending while doing nothing to actually address those issues has pretty much killed that bill in the current Congress. There are other past proposals that could put us on the right path—well, they did when introduced—but Republicans are, sadly, paying much more attention to culture wars and cutting nondefense spending than actually addressing the predictable debt crisis that we’re facing.