The Criticism of the Fiscal Commission Act Ignores America’s Perilous Fiscal Future

The Clock Is Ticking

This post was originally published at FreedomWorks.org on February 5, 2024. It has been posted at Exiled Policy with minor modifications.

Recently, the House Budget Committee marked up the Fiscal Commission Act, H.R. 5779, on a bipartisan basis. The Fiscal Commission Act would create a commission, comprised mostly of Members of Congress and outside experts appointed by congressional leadership, to make recommendations to address the structural budget deficits and rapidly growing share of the federal debt held by the public.

The goal of the commission would be “to improve the fiscal situation in the medium term and to achieve a sustainable debt-to-GDP ratio of the long term, and for any recommendations related to Federal programs for which a Federal trust fund exists, to improve solvency for a period of at least 75 years.”

The need for the commission is evident. The Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund will reach depletion in 2031, while the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund will be exhausted in 2033. Benefit cuts for current beneficiaries are a certainty in the event that Congress does nothing. Additionally, the debt-to-GDP ratio is around 100 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and is projected to reach 180.6 percent in the next few decades.

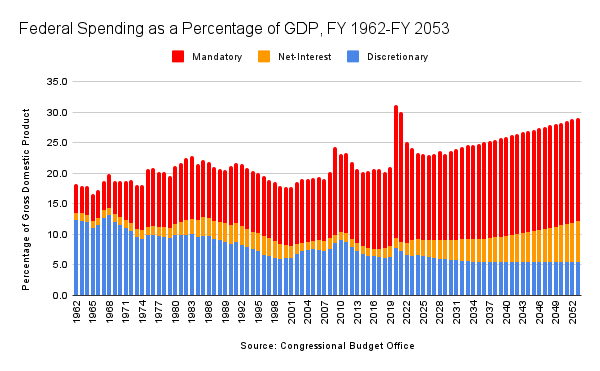

Over the next 30 years, federal spending is projected to grow from the 23.4 percent of GDP projected in FY 2024 to 29.1 percent in FY 2053. The deficit is projected to rise from 5.8 percent of GDP to 10.0 percent of GDP. The share of the debt held by the public could reach nearly 181 percent of GDP. These are the rosiest scenarios provided by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). There are alternative scenarios in which spending reaches 37.7 percent of GDP in FY 2050 and the share of the debt held by the public hits 250 percent. The drivers of deficits and debt are trust fund programs and net interest on the national debt.

As a result of these deficits and debt, Congress will borrow more to finance its spending. Within the next 20 years, 30 percent of federal spending will be borrowed. We’re borrowing $1 trillion every 140 days.

Rep. David Schweikert (R-AZ) recently said, “Every dime a Member of Congress votes on is borrowed. Plus, congratulations. It looks like every dime we vote on is borrowed plus another trillion dollars[.].” Around a quarter of our debt is held by foreign countries, with Japan, an ally of the United States, being the largest holder of our debt. However, China is the second largest holder of our debt.

These are the facts. Few dispute them.

Unfortunately, there has been a concerted effort by some, particularly in the conservative movement, to try to stop the Fiscal Commission Act from reaching the floor. The criticism is that a fiscal commission would be a vehicle for tax increases because the Fiscal Commission Act includes language that would require the commission to “propose recommendations that meaningfully improve the long-term fiscal outlook, including changes to address the growth of direct spending and the gap between the projected revenues and expenditures of the Federal Government.” This is the only mention of revenues in this context in the bill.

The opposition to the Fiscal Commission Act borders on the irrational for different reasons.

The Fiscal Commission and Congress Would Have to Approve Any Recommendations

The commission would be comprised of 16 members—12 of whom would be elected Members of Congress and four outside experts. Hearings would be held, and members of the commission would develop and vote on recommendations. Each committee in Congress can send recommendations to the commission. Outside groups, can offer feedback or express policy preferences.

The way the commission would handle recommendations isn’t difficult to grasp. The commission would have to approve the recommendations by a simple majority that must include at least three Republicans and three Democrats to be adopted. The recommendations would be sent in the form of a report to the President, the Senate majority leader, the Senate minority leader, the Speaker of the House, the House majority leader, and the House minority leader. Legislative language and cost estimates for the recommendations are also required with the report.

A common and misleading talking point is the Fiscal Commission Act would hand over Congress’s power to the commission. That’s simply not true. Both chambers of Congress—the House and the Senate—have to vote on the legislative language of the recommendations. If that legislation manages to clear both chambers, it still has to be signed into law by the President.

Some have complained about the expedited consideration that the Fiscal Commission Act would provide for the report of the commission. The implication is that expedited consideration is irregular or nefarious in some way. That’s just nonsense.

Congressional Republicans, for example, have often used expedited consideration in the Senate via disapproval resolutions through the Congressional Review Act. These “CRAs,” as they’re known in legislative vernacular, are privileged—meaning that they’re not subject to the three-fifths cloture threshold—and require only a simple majority vote to move through the Senate.

Although the report of the commission wouldn’t be subject to amendment in the Senate, the process is similar to budget reconciliation, which was used to pass the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017. There are differences between budget reconciliation and how the commission’s report would be handled, for sure, but the topline of expedited consideration is the same. (It’s also worth noting that increasing taxes can be done through budget reconciliation by a simple majority in the Senate. Changes to Social Security, however, can’t be done through budget reconciliation. See 2 U.S.C. §641(g).

The legislative language isn’t amendable in the House, but that has often been the case over the past several years through the use of closed rules that provide for the consideration of legislation. Rules have also been used to waive points of order against bills, among other examples.

This criticism of the Fiscal Commission Act borders on the absurd. Expedited consideration isn’t necessarily out of the ordinary, nor is it nefarious.

There Can’t be Preconditions for a Fiscal Commission

The second reason opponents of the Fiscal Commission Act have it wrong is that some want to take any discussion of revenues off the table. The fiscal state of the nation is untenable, to put it diplomatically. To even begin conversations on this extraordinarily difficult topic, preconditions are a nonstarter.

Democrats on the House Budget Committee offered amendments to have the commission specifically consider raising taxes on individuals who earn $400,000 or more and to prohibit changes to Social Security. These amendments were defeated precisely because preconditions would’ve killed the Fiscal Commission Act in its tracks.

Some in the conservative space wanted preconditions related to revenues or have criticized and continue to criticize the Fiscal Commission Act for not excluding revenues from consideration by the commission. Revenues have always been a significant point of contention when similar commissions or committees have taken on the task of trying to address structural deficits. The arguments, especially recently, are that increased revenues will slow economic growth and that Congress doesn’t lack revenue.

Revenues have never exceeded 20.5 percent of GDP, and that came in FY 1944 during World War II. Six of the top ten years of revenues measured by GDP have occurred since FY 1997. Four of those years were FY 1997, FY 1998, FY 1999, and FY 2000. At the time, the top marginal income tax rate was 39.6 percent. Annual economic growth in those four fiscal years exceeded 4 percent.

Looking at CBO projections, revenues are expected to grow. However, even with a growth in revenues enough to crack the top ten, it’s not enough to keep pace with Medicare and Social Security spending and net interest on the debt. Tax increases discourage productivity, savings, and investment. These are particular points that Congress must keep in mind as it approaches addressing these issues.

Tax revenues have been on the upswing in recent years and are projected to grow even higher. Granted, one of the reasons tax revenues are projected to grow is the expiration of the individual tax cuts and reforms under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Revenues are projected to jump from 8.8 percent of GDP in FY 2024 to 9.7 percent in FY 2027. Meanwhile, corporate tax revenue is projected to decline from 1.8 percent of GDP in FY 2024 throughout the next decade to 1.4 percent of GDP in FY 2031. Payroll tax revenue is projected to remain relatively stable, between 5.9 percent of GDP and 6.0 percent of GDP. Revenues are projected to rise past FY 2033, reaching 19.1 percent of GDP in FY 2053.

We’ll note that the average revenues from FY 1944 through FY 1980 was 17.2 percent of GDP. Some may point out that this was a period of historically high marginal income tax rates. That’s accurate. However, there were plenty of ways to avoid such high levels of taxation, which is why, despite top margin rates exceeding 90 percent, tax revenues as a percentage of GDP are lower than they are today.

Still, tax revenues are higher today than they were from FY 1981 through FY 2000, which, beginning in 1986, was a period of markedly lower top marginal tax rates. The tax reforms passed under President Reagan eliminated many of the carveouts in the tax code and used that revenue to lower tax rates. (Showdown at Gucci Gulch: Lawmakers, Lobbyists, and the Unlikely Triumph of Tax Reform by Jeffrey Birnbaum documents the passage of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and is required reading for discussions of tax policy and tax reform.)

The problem we face today isn’t on the revenue side. It’s spending. Unfortunately, those who focus on spending ignore what’s driving budget deficits and debt. It’s not discretionary spending, folks. That’s what nearly every conservative rails about inside and outside of Congress.

The drivers of deficits and debt are trust fund programs and interest on the debt. We can debate it all day, but all one needs to do is look at discretionary spending, both current and projected, and compare it to mandatory spending and net interest to see the problem.

We are very quickly heading into a death spiral because of our fiscal profligacy. We may already be there.

Some may say that Congress should focus on reducing “waste, fraud, and abuse” in trust fund programs. Improper payments are an issue in Medicare and Social Security. Congress must continue to address this issue, but improper payments aren’t the source of structural problems that trust fund programs face.

Looking only at Medicare, improper payments represent 6.3 percent of the $818.9 billion in Medicare outlays. In addition to the nearly $104 billion in total improper payments for Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP, Social Security has failed to recover $23 billion in improper payments. While improper payments represent significant sums, the budget deficit in FY 2023 was $1.69 trillion. Put simply, it’s an unserious view to claim that improper payments are the sole problem.

Simply put, there can’t be a real and meaningful discussion of how to address our fiscal problems if the Fiscal Commission Act ties the hands of the commission it would create. Creating the commission requires bipartisanship. That’s just a fact.

Another fact is that any recommendations that have even the slightest chance of being adopted have to be bipartisan. In an era of hyperpartisanship, “bipartisan” is often considered a dirty word. However, any solutions to the serious fiscal issues that we face have to be bipartisan to: a) get through Congress and b) have any credibility with the American people. This last point is particularly important.

The margins in our politics will always complain about major legislation passed on a partisan basis. The margins will often complain about bipartisan legislation passed by Congress. There’s no getting around that. But to have credibility with those who aren’t on the margins—which is the plurality of Americans—the solutions must be bipartisan. Anyone—Republican or Democrat or conservative or progressive—who says we can address these issues without bipartisanship cannot and should not be taken seriously.

We Have a Responsibility to Engage a Fiscal Commission

Advocating against a fiscal commission has to be awkward. Imagine walking into a congressional office or emailing a congressional staffer and telling whoever you’re talking to that their boss should vote against the Fiscal Commission Act because it doesn’t provide explicit protection for Social Security as it currently exists or doesn’t take revenues off the table. Essentially, what you’re doing is lobbying for the status quo, which, according to the CBO, is at best a managed decline and at worst a painful fiscal crisis.

Every year, the Bureau of the Fiscal Service releases the Financial Report of the United States Government. The most recent report was for FY 2022, so some of the facts and figures are out of date. That being the case, the picture hasn’t gotten any better since it was released. As the report states, “The current fiscal path is unsustainable.” That’s a diplomatic way to put it. Here’s what else the report says, “In the FY 2022 Financial Report, the debt-to-GDP ratio for 2095 is projected to be 552 percent[.]”

Obviously, the years mentioned in the report are a long way off, so there’s plenty of time to course correct, but the question that has to be asked to opponents of the Fiscal Commission Act is, how much pain do you prefer we endure before we address our serious and encroaching fiscal problems? Another question: Can we tackle these issues before it bankrupts our economy and ruins lives?

The commission will almost certainly provide an opportunity for advocacy organizations and single-issue special interest groups to provide feedback and recommendations.

Supporting the Fiscal Commission Act does not mean that one is endorsing the recommendations that the commission may eventually produce. Free marketers, including myself, have policy recommendations that they are prepared to make related to trust fund programs and other mandatory spending programs. I would like to see changes to modernize Social Security and Medicare for those who haven’t reached retirement age. However, I understand the necessity of ensuring that those who rely on Social Security and Medicare don’t see changes to their benefits. The same goes for those who are reasonably close to retirement age.

A Fiscal Commission May Not Achieve Success But We Should Hope It Works

One of the arguments we’ve seen, almost exclusively from conservative groups, is that past fiscal commissions have proposed tax increases. The National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (otherwise known as “Simpson-Bowles,” after its co-chairs, Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles) proposed $4 trillion in deficit reduction over ten years. Part of the proposed deficit reduction relied on significant revenue increases, much of which came from the proposed limitation or elimination of tax deductions, expenditures, and other loopholes in the tax code. The largest tax increase was the changes to the payroll tax.

Although a majority of members of Simpson-Bowles adopted a report, the recommendations in the report were rejected by Congress in March 2012.

Another commission was the United States Congressional Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction. This “super committee” was created by the Budget Control Act of 2011. Unlike Simpson-Bowles, the super committee wasn’t able to reach an agreement on recommendations. Revenues were a sticking point for the super committee. As aside, similar expedited procedures for consideration in the House and the Senate were included in the Budget Control Act if the super committee did reach an agreement.

If the Fiscal Commission Act is passed, the commission it creates will have the odds stacked against it. That much is clear. History tells us as much. Still, the fiscal situation today is substantially worse than it was when Simpson-Bowles and the super committee considered these issues. Does that mean the result will be different? No one can say with any certainty.

Those of us who support the Fiscal Commission Act hope that any future commission will approach our fiscal issues with a measure of seriousness and commitment. We should hope for success. We cannot ignore our fiscal woes out of existence. Our future is riding on it.