The Debt Ceiling Drama

What House Republicans Want in Exchange for a Debt Limit Increase

House Republicans haven’t formally rolled out their offer to President Biden to increase the debt limit, but Punchbowl News recently reported the details of the proposal. As mentioned in Punchbowl’s newsletter on Monday, the proposal would “cap non-defense discretionary spending at $584 billion; limit budget growth to 1% annually for the next 10 years; prohibit student loan forgiveness; repeal green tax credits; institute work requirements for social programs; enact H.R. 1, the large-scale energy package the House GOP pushed through the chamber last month; and pass the REINS Act, which is designed to reduce federal regulation.”

Before we dive into the politics of all of this, let’s look at the policies. What has been proposed isn’t insignificant, but it won’t come close to balancing the budget. Republicans would have to trim $1.576 trillion in spending to balance the budget, and these proposals just aren’t going to do that. That’s not to say what Republicans want in exchange for a debt limit increase wouldn’t make a dent in the deficit.

A cap on nondefense discretionary spending of $584 billion in FY 2024 with a 1 percent increase each fiscal year after, using the February 2023 Congressional Budget Office baseline, amounts to a roughly 43 percent cut in nondefense discretionary spending and a 24 percent cut to overall discretionary spending in FY 2024 and 27 percent in FY 2033.

That said, it’s a really bad look to exempt defense discretionary spending, which is projected to be $848 billion in FY 2024. There are literally plenty of examples of waste in defense spending that Congress never quite seems to have time to eliminate. Let’s face it, folks. The military-industrial complex has its teeth so far in Congress’ neck that it would make Dracula blush.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the Lower Energy Costs Act, H.R. 1, would reduce the budget deficit in the short term by $11.6 billion but increase it by $43 million over ten years. The repeal of “green tax credits” is vague, but it’s probably safe to assume that this means the repeal of part of the Senate Committee on Finance portion of the Inflation Reduction Act, which would presumably be most of, if not all Title I, Subsection D of the law. That would save $205.2 billion over ten years. Prohibiting student loan forgiveness would save another $400 billion over ten years. However, the fate of the student loan forgiveness executive action is already in legal limbo.

The REINS Act is designed to curb regulation. Rather than disapproving a regulation under the Congressional Review Act, Congress would have to approve economically significant regulations (those with an annual cost of $100 million or more) before they can take effect. There’s not much on the budgetary impact from the CBO, but the 2017 cost estimate stated that the REINS Act “would have significant effects on both direct spending and revenues.” Those effects weren’t quantifiable.

Finally, “work requirements for social programs” is likely a reference to work requirements for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), otherwise known as “food stamps.” House Republicans passed this policy as part of Title IV of their version of the 2018 farm bill. Now, this particular title represents much of farm bill spending because of SNAP. House Republicans included work training programs that largely erased the savings from the work requirements.

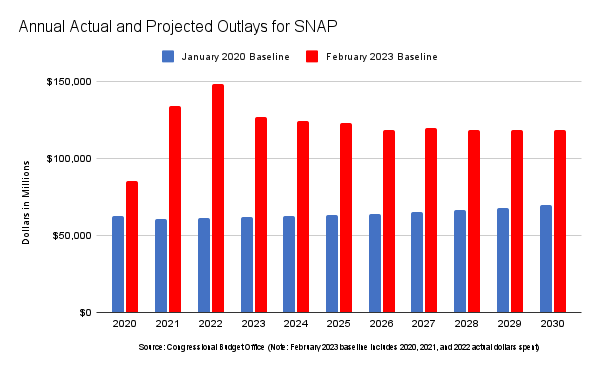

In the January 2020 baseline, outlays for SNAP were projected to be $62 billion in FY 2023. Pandemic-related legislation boosted SNAP outlays, with 33.3 million people projected to receive an average of $133.44 in monthly benefits. As a result, in the most recent baseline, SNAP spending is projected to be $127 billion in FY 2023, with 41.3 million people expected to receive an average of $222.02 in monthly benefits.

When I was at FreedomWorks, I wrote a memo in August 2017 in which I proposed including the REINS Act, along with a Swiss-style debt brake, in a debt limit package. At liberty of being called a hypocrite, I, along with others, brought these ideas to the White House on two separate occasions five or six months before I wrote that memo, which was meant to be an internal document. I found out after that the memo was sent to someone at the White House (I don’t know who), who then leaked it to Politico.

By the time the memo was written, the writing was also on the wall. We all knew that we were going to lose when Congress took up the issue, and that’s exactly what happened in September 2017 and again in March 2018 when Congress suspended the debt limit. By the way, at the time, there was a Republican in the White House and a Republican-controlled Congress. All we got was the Joint Select Committee on Budget and Appropriations Process Reform, and its recommendations didn’t go anywhere. No surprise.

Going back even further to the 2011 debt limit debate, the Budget Control Act was the product of then-Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) and President Obama and their top aides directly negotiating. It began with the “grand bargain” and ended with the Budget Control Act, which was routinely ignored by both parties.

Some may say, “Well, Republicans had only the House. Obama was in the White House and Democrats had the Senate in 2011. Republicans still pulled off spending cuts.” Yes, Republicans had control of the House, but it’s an overly simplistic view. The politics were very different than today.

In the 2010 midterm election, Republicans picked up a net 63 seats in the House and six seats in the Senate. That’s a “red wave.” President Obama conceded that it was a “shellacking.” In the 2022 midterms, Republicans picked up only nine seats in the House, giving them a four-seat majority, and lost a Senate seat and remained in the minority. It was supposed to be a red wave, but it looked more like a small ripple.

Obviously, a combination of candidate quality, the ex-president and all of his drama, and the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs are reasons why Republicans failed to capitalize in 2022. It’s quite possible that each of those could again be problems for the red team in 2024.

On one hand, the strategy here is puzzling. On the other hand, it’s entirely predictable. It’s puzzling because with such a tenuous grip on power in the House, if Republicans push too hard, and the federal government defaults on its debt, it’ll backfire on them. Look at government shutdowns, for instance. I can think of only one time in recent memory when a government shutdown even marginally helped Republicans. That was the January 2018 shutdown.

We already may be sliding into a recession, and default will almost certainly guarantee that we will go into an economic downturn. Will that downturn be the apocalyptic scenario that some have predicted? As I wrote back in January, I don’t know, but I don’t want to find out.

It’s entirely predictable because McCarthy isn’t exactly in a position to simply give the White House a clean debt limit increase because his conference has drifted so far to the right. I don’t think McCarthy would’ve given a clean debt limit increase, but I don’t think he would’ve demanded this much if his conference was truly interested in making a deal. Conservatives would undoubtedly say that they want a deal and point to these demands as evidence of that. I’m sorry, but this isn’t a serious proposal, and anyone who makes this argument knows it.

Republicans have to know that everything they want is a nonstarter with Democrats from a policy perspective. By the sound of it, McCarthy may not have the votes in his own conference. While I support most of the policies that Republicans are pushing here, I very much question the wisdom of trying to leverage the debt limit this way in this exceedingly toxic political atmosphere with so much on the line as the economy is already teetering on a recession.