Analyzing the CBO's Estimate of OBBBA

The True Cost of OBBBA Could Exceed $4.3 Trillion

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released the complete cost estimate of the so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA), H.R. 1, as passed by the House on May 22. The cost estimate shows a total hit to the deficit of $2.416 trillion from FY 2025 through FY 2034. That’s $3.670 trillion in projected reductions in revenue and $1.254 trillion in spending cuts over ten years.

Republicans are resting on a theory that OBBBA will increase economic growth to the tune of $2.6 trillion over the ten-year budget window. By their math, OBBBA would theoretically pay for itself. There is no reason to believe that it would, as evidenced by projections from the Penn-Wharton Budget Model and the center-right Tax Foundation. Penn-Wharton projects an increase in the budget deficit of $4.553 trillion over ten years while the Tax Foundation estimates a $1.724 trillion increase in the budget deficit.1 That’s a significant range, no question, but even under the rosier lens of the Tax Foundation, OBBBA substantially increases the budget deficit.

Although some House conservatives fought to expedite the work requirements for social programs like Medicaid and food stamps, only 30 percent of the deficit reduction in OBBBA occurs from FY 2025 through FY 2029. The remaining deficit reduction—70 percent of the spending cuts in the bill—occurs after FY 3030.

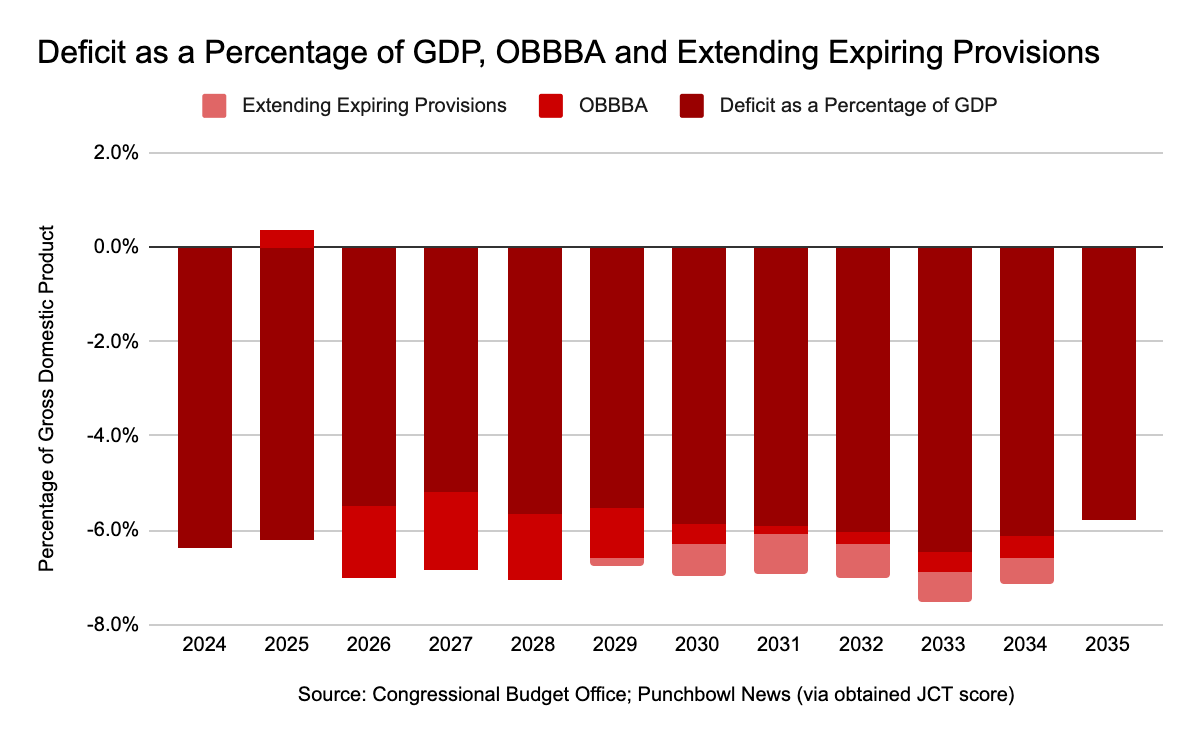

You also have to consider, as I recently mentioned, that 16 provisions of OBBBA will expire in FY 2029 or later. The expiring provisions include the temporary enhancement of the standard deduction, the temporary enhancement of the child tax credit, the exclusion of tipped wages from income taxes, the exclusion of overtime wages from income taxes, and the additional deduction for seniors. The deficit impact of extending these provisions from FY 2029 through FY 2034, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT), is $1.427 trillion.2

Not included in the CBO’s estimate of OBBBA are interest costs. The CBO estimates $551 billion in net interest costs from FY 2025 through FY 2034.3 The share of the debt held by the public would increase to 123.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in FY 2034 compared to the 117.1 percent projected for the same fiscal year in January 2025.

The table below shows the CBO estimate on a committee-by-committee basis. I’ve included the CBO estimate of interest costs and the JCT estimate of extending provisions that begin to expire in FY 2029. My math shows a net impact on the deficit of $4.394 trillion over ten years. The JCT deficit impact doesn’t include net interest costs, so the true cost of those policies, if extended, probably means the deficit impact of OBBBA exceeds $4.6 trillion. Also, don’t assume the increased spending in the Armed Services’ recommendations is phased out as quickly as the CBO assumes.

Although the deficit would decline in FY 2025, it would dramatically increase in FY 2026, eventually exceeding $3 trillion in FY 2033. Under the CBO’s January 2025 baseline, the federal government doesn’t reach $3 trillion deficits until FY 2039, so we’re talking about a significant acceleration of deficits and debt.

The deficit as a percentage of GDP would reach 7 percent in FY 2026 and hover in that ballpark. Eventually, in FY 2033, it would reach 7.5 percent of the economy. Now, the CBO baseline assumes the yield on the ten-year Treasury would be 4.113 percent in Q2 of calendar year 2025. We are in the final month of Q2, and the current yield stands at 4.506 percent. In other words, deficits are already higher than projected. Adding trillions of new debt isn’t going to make that any better.

I’ll say once again that I’m not against tax cuts. I lobbied in support of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act while at FreedomWorks. The fiscal situation the United States finds itself in today is precarious and urgent. What OBBBA does, and what it could do if provisions are extended, is take a perilous situation and make it substantially worse. I’m aware of the CBO’s cost estimate of increased tariffs, which shows $2.8 trillion in additional revenue over ten years.4 That doesn’t significantly improve the situation, because the tariffs, as CBO explained, will reduce GDP. That estimate also doesn’t account for the substantial uncertainty caused by the administration’s pauses of the tariffs.

It’s hard to avoid the obvious conclusion. OBBBA is fiscally irresponsible, and that’s a diplomatic way of putting it.

Penn-Wharton and the Tax Foundation estimates account for macroeconomic effects. Neither estimate accounts for net-interest costs.

The deficit increase from FY 2029 through FY 2034 was calculated. I intentionally left FY 2035 from the math because CBO’s budget range for OBBBA is FY 2025 through FY 2034.

CBO provided this information in a letter to Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR) but did not include the year-by-year budgetary impact.

The estimate accounts for reductions in net interest costs and macroeconomic effects.