House Appropriations Is Trying to Gut the Government Accountability Office

GAO has saved taxpayers $725 billion since 2011. Why reduce its funding?

Much ink has been wasted on the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). The pet project of Elon Musk has found some $190 billion in savings since January. How much of that is real is anyone’s guess.1 The so-called “wall of receipts” has been littered with errors, casting doubt on the total claimed savings.2

Congress already has a watchdog agency that identifies waste and duplication in federal spending while also promoting efficiency. That’s the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Created in 1921, the GAO is one of a handful of federal agencies housed inside the Legislative Branch. Like the Congressional Budget Office and the Congressional Research Service (CRS), the GAO is nonpartisan, and its recommendations are proposed based on careful study or investigations.

GAO has a track record of success. Since 2011, the GAO has saved taxpayers $725 billion. There’s at least another $100 billion in savings on the table if Congress and federal agencies in the Executive Branch adopt existing recommendations. Unlike DOGE, GAO's assertions of taxpayer savings are backed up by hard data. And just so you know I’m not relying solely on GAO’s own accounting, Dan Lips of the Foundation for American Innovation has looked at the track record of GAO. In September 2021, he wrote, “The taxpayer dollars that Congress spends on the Government Accountability Office each year generates a large return-on-investment. But additional savings and government improvements could be achieved if agencies implanted all of GAO’s open recommendations and acted on future recommendations in a timely manner.”

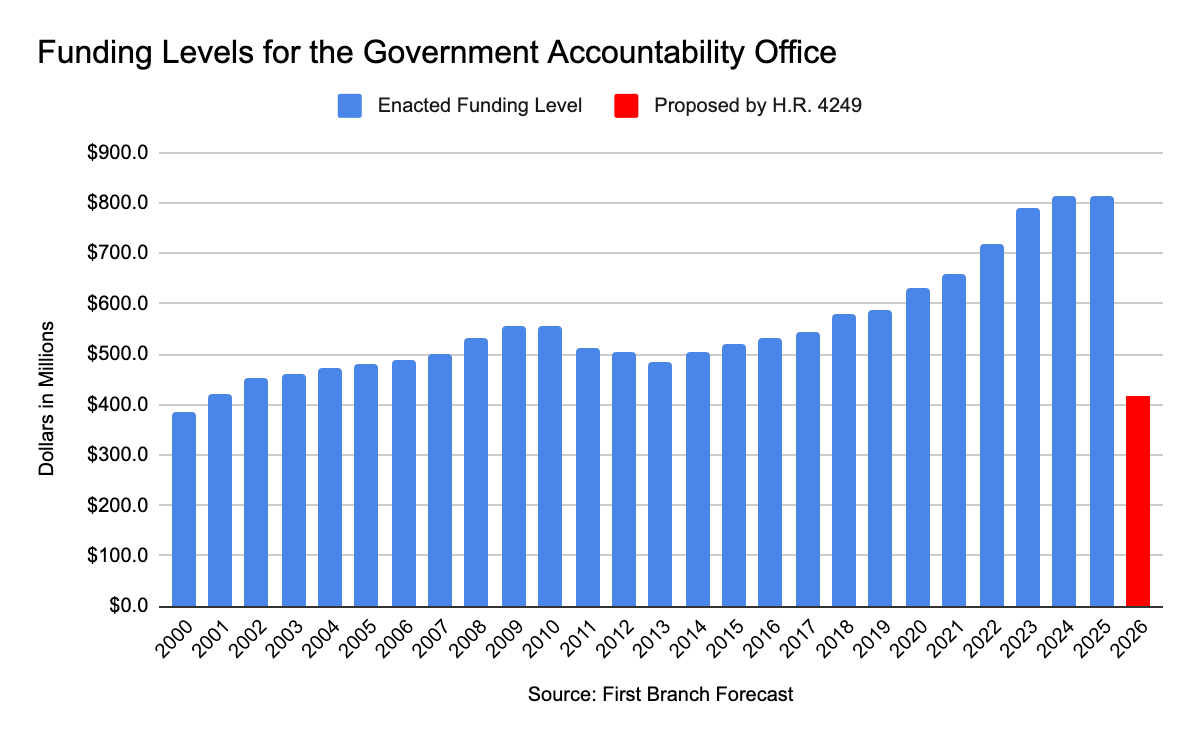

Not bad for an agency that received an appropriation of nearly $812 million in FY 2025. That's a lot of money, until you realize that GAO's savings each year amount to tens of billions of dollars. Of course, GAO isn’t driven by partisanship. The oversight the agency provides doesn’t grab a bunch of headlines. They are responsive to requests from Congress, however, and sometimes the conclusions that the GAO draws ruffle feathers, particularly during this era of hyper-partisan politics. They are an equal opportunity offender. The value of GAO and other agencies in the Legislative Branch should convince Congress to increase funding for them as an investment in a more efficient and accountable government.

Congress Failing to Invest in Itself Consolidates Power in the Wrong Places

Without going down too much of a rabbit trail, the Legislative Branch has notoriously failed to invest in itself. In fact, in the ‘90s, Congress cut its own funding. When Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-GA) took control of the House in 1995, he eliminated the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) and cut funding to GAO and CRS. These and other cuts to the Legislative Branch were part of the “Contract with America”–the campaign platform that Republicans campaigned on during the 1994 midterm elections.

When we talk about what’s wrong with politics today, it’s hard not to see many of our problems being born in this era. The elimination of OTA and the cuts to GAO and CRS weakened congressional capacity, pushing congressional staff to rely more on lobbyists and outside groups. When we think of oversight, we often think of committees and subcommittees looking into various matters.3 However, oversight is also conducted by GAO while CRS provides vital research on policy and process matters.

Congress effectively gutting itself has been good for congressional leadership, which has consolidated more power in its hands. It’s also good for the Executive Branch, which continues to blur the lines between the separation of powers.

It’s clear that Congress faces significant budgetary challenges, particularly following the passage of the tax bill and the impending insolvency of Social Security and Medicare. GAO has repeatedly warned that America's fiscal health is at risk. Discretionary spending has been and will continue to be crowded out by mandatory spending and net interest. It’s just a reality. The fact is that the Legislative Branch is a separate, not subservient, branch of government. It’s the “first branch.”4 Yet, about 0.4 percent of discretionary spending goes to the Legislative Branch.5

Why Would Congress Want to Gut GAO?

Unfortunately, the House Appropriations Subcommittee on the Legislative Branch plans to slash funding to the GAO in the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act, H.R. 4249, by almost 50 percent, to $415.4 million.6 GAO was funded at nearly $812 million in FY 2024 and FY 2025.

There’s simply no good or justifiable reason to cut GAO. None. So, why is an appropriations bill advancing that would have a devastating impact on GAO? I’ll give you three guesses, but you’re only going to need one. In April, it was reported that the GAO had 39 investigations into impoundment actions.7

The GAO also sent a letter to the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), Russ Vought, informing him that OMB had illegally taken the apportionments website offline. The apportionments website provides a central location for the government and public to understand how tax dollars are being spent. It is central to ensuring that money is being spent responsibly and in accordance with the law.

The Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act for FY 2022 requires OMB to post documents apportioning an appropriation on a website no later than two days after such an apportionment is approved.8 The Financial Services and General Government Appropriations Act for FY 2023 required OMB to make these data available for FY 2023 and each subsequent fiscal year.9

Another political motivation for the funding cut is that GAO issued an opinion finding that OMB’s impoundment of funds obligated for Ukraine aid in 2019 was illegal. Although this opinion wasn’t issued until January 2020, almost a month after Trump was impeached, it helped shape the narrative during the Senate trial. Vought, who ran OMB for part of Trump’s first term, has mentioned GAO in the context of the first impeachment of Trump after the watchdog agency found that the administration recently violated the Impoundment Control Act. Vought claimed GAO “played a partisan role in the first-term impeachment hoax.”

Vought has a weird theory that the Impoundment Control Act is unconstitutional, so he’s treating it as if it doesn’t exist. The Supreme Court hasn’t directly weighed in on the constitutionality of the Impoundment Control Act,10 but it has touched on the intent behind it in Train v. City of New York (1975) and Clinton v. City of New York (1998).11

A Continuing Resolution Is a Danger to GAO

Let’s assume that Congress enacts a short-term continuing resolution (CR) by October 1 until some point in December. The odds of that are high. The House has put forward a figure of $415.4 million for GAO. While we don’t know what the Senate Appropriations Committee will do yet, let’s say it meets GAO’s $934 million budget request.

Typically, we think of a CR as carrying over the funding rate from the previous fiscal year as a stopgap until an appropriations bill is enacted. That’s accurate. That’s what a CR does. However, agencies don’t necessarily operate in that manner. During a short-term CR, as this CRS report explains, agency spending could be based on another methodology stipulated in the text of the bill. Congress could legislate the rate at which an agency can expend funds. However, this is a CR, so they're copying and pasting last year's numbers. An agency can expend funds, but it must try very hard not to spend at a higher rate than Congress will appropriate in a regular appropriations bill.

So what do agencies do? Generally speaking, they follow OMB guidance. OMB guidance is that each agency should spend funds at the lowest rate likely to be approved by Congress. So they look at the bill passed by the House, the bill passed by the Senate, and last year's number, and choose the lowest number as the expected final appropriation.

How would this work in practice during a temporary Continuing Resolution? If the House has passed a regular appropriations bill setting the final number at $415 million, and the Senate passed a regular appropriations bill at $934 million, and Congress last year appropriated $890 million, the agency will treat the $415 million amount as the guideline by which they will spend funds during the CR. Normally, there isn't such a wide disparity between these numbers. But these aren't normal times.

Obviously, that’s a difference of hundreds of millions of dollars, which will result in mass layoffs at GAO and an inability to serve its core functions.

What Happens Next?

The Legislative Branch Subcommittee marked up the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for FY 2026 on Monday, June 23. The full House Appropriations Committee did a separate markup of the bill on Thursday, June 26. The Legislative Branch Appropriations Act isn’t likely to come up when the House returns the week of July 14. The bill may be considered before the August recess. The Senate is scheduled to markup its version of the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act on Thursday, July 10. They're skipping the subcommittee markup and moving straight to the full committee.

What will happen is anyone's guess, but cooler heads often prevail in the Senate. The House's proposal is wildly radical and irresponsible. Ultimately, the two chambers will have to reach some kind of agreement. If not, we're looking at a CR or a government shutdown.

Update: The Senate Appropriations Committee’s Legislative Branch Appropriations Act funds GAO at $812 billion in FY 2026. The panel approved the bill on July 10.

It ain’t even close to $190 billion, folks. DOGE has consistently wildly overstated the amount saved.

I’m not saying the idea of DOGE was bad. The potential to root out wasteful spending that GAO isn’t focused on and shutter unneeded federal properties/leases is a good idea. DOGE’s focus on hot-button issues, erroneous or redundant claimed savings numbers, and other problems unnecessarily politicized its work.

Often politically motivated oversight. Rarely will you see a committee conduct oversight if the majority party also has control of the White House.

With apologies to my friend, Daniel Schuman, who runs the First Branch Forecast.

The Legislative Branch has the lowest total appropriation of the 12 regular appropriations bills. H.R. 1968 provided $6.742 billion to the Legislative Branch in budget authority. The 302(b) allocation for the Legislative Branch for FY 2026 is $6.7 billion, but the budget authority for FY 2026 in the actual appropriations bill is $5.01 billion.

You’ll have to scroll down to the relevant part of the committee report or do a “Ctrl+F” search. The text of the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for FY 2026 is available here.

Impoundment is the withholding of money appropriated by Congress. The act of impoundment isn’t in and of itself illegal. However, the act of permanently withholding obligated funds is illegal.

See the statutory notes for Pub. L. 117–103, div. E, title II, §204(b), Mar. 15, 2022, 136 Stat. 257 at 31 U.S.C. §1513.

See the statutory notes for Pub. L. 117–328, div. E, title II, §204, Dec. 29, 2022, 136 Stat. 4667 at 31 U.S.C. §1513.

Oddly enough, a friend texted me after I published yesterday’s post and asked me to write an explainer on the Impoundment Control Act before I began writing this piece. Andy, I’ll try to do that in the coming days.

There’s a lot more to discuss in these two holdings by the Court. Train was narrow, but Justice Antonin Scalia’s dissent in Clinton v. City of New York, in which the Court found the Line Item Veto Act unconstitutional, validates the point and suggests Train may be considered more reaching. Scalia wrote, “Congress may confer discretion upon the Executive to withhold appropriated funds, even funds appropriated for a specific purpose.”

As always….thank you for writing articles that are timely and relevant to what’s happening. Looking forward to your future article on The Impoundment Control Act.