Increasing the SALT Cap Only Benefits High-Tax States

Higher-Income Households Also Benefit From Increasing the Cap on the Deduction

One issue holding up the tax bill in the House is that a handful of Republicans want to lift the cap on the state and local tax (SALT) deduction. That cap was set at $10,000 under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, and it wasn’t indexed to inflation. Prior to the cap, individuals could fully deduct their state and local income taxes, state and local real estate taxes, and state and local personal property taxes.

I mentioned on Sunday that I hate the SALT deduction. More specifically, I’m not a fan of tax deductions and credits. In a perfect world, Congress would create a flat tax with a generous standard deduction. The closest we’ve come to a flat tax, though, was tax years 1988 through 1990. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 established two marginal income tax rates, 15 percent and 28 percent. Unfortunately, President George H.W. Bush signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, breaking his “no new taxes” pledge. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act created a third marginal income tax rate of 31 percent. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, signed by President Clinton, created five marginal income tax rates, with the highest at 39.6 percent.1

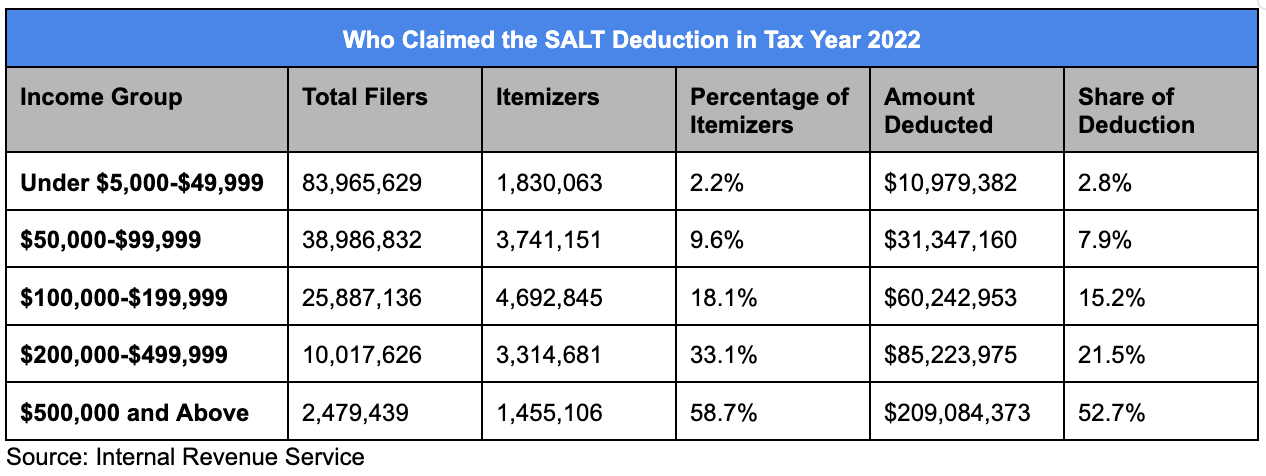

Getting back to the issue at hand. I loathe the SALT deduction because it is, in effect, a subsidy for high-tax states. In tax year 2017, 46.8 million tax filers itemized in tax year 2017, or 30.3 percent of all tax filers, and deducted $1.4 trillion from their income. Look, the more money you earn, the more likely you are to itemize rather than take the standard deduction. Still, the data tell us that the SALT deduction overwhelmingly benefits people in higher-income households. According to the data from the Internal Revenue Service, 78.4 percent of the value of the SALT deduction went to filers who had an adjusted gross income of $100,000 or more.

Taxpayers in three states–California, New Jersey, and New York–represent 21 percent of those who itemized in tax year 2017. That’s 9.861 million returns, which, in total, allowed these taxpayers to deduct $166.9 billion from their income, or roughly 27 percent of the $624.8 billion deducted through SALT. These are states that tend to have higher per capita expenditures than the national average, allowing them to raise taxes with the knowledge that higher-income taxpayers can simply deduct their state income taxes on their federal taxes.

That was before the $10,000 SALT cap took effect.

In tax year 2022, only 15 million tax filers used the SALT deduction, reducing their income by $397 billion. Although the data show increases in some data points, you have to look at them in the context of a significantly more generous standard deduction. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act roughly doubled the standard deduction from $6,350 for an individual filer and $12,700 for a married couple filing jointly to $12,000 and $24,000. That change was indexed to inflation. In tax year 2024, the standard deduction for an individual and a married couple filing jointly was $14,600 and $29,200.

One of the primary goals of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was tax simplification. Of course, that doesn’t appear to be the goal of the new tax bill that the House may soon consider. There are a number of provisions that make the tax code more complex. Also, increasing the SALT cap at a time when the federal government is running deficits approaching $2 trillion is just a horrible idea. Increasing the SALT cap isn’t cheap. It will increase the deficit impact of a tax bill that is already likely to increase deficits by a couple of trillion dollars over the next ten years.

This is as far as I’m going with the recent history of tax rates.