Partisan Redistricting Drives Polarization in Congress

The moves to redraw congressional district lines in Texas and California have placed new emphasis on the partisan redistricting process in most state legislatures.1 Typically, redistricting occurs after the completion of the decennial Census. In the majority of states–33, to be exact–the legislature has primary control over redistricting while ten states use independent commissions. Four states have a hybrid system or political commissions. The remaining three states only have one representative in the House, so redistricting isn’t necessary.

As our politics have become increasingly hyper-partisan, Republicans and Democrats have sought to increase their political power in the House by ensuring they have as many congressional districts as possible. This leaves about 40 seats that can be considered competitive in any given election cycle.2 When you think about this, it’s absolutely nuts considering that independents are a plurality of voters today.3

What is being considered in Texas and California only underscores that we live in a hyper-partisan age, in which the interests of the red team and the blue team are put ahead of what is best for the country. The difference is that it’s out in the open, not subtle. It’s naked partisan politics. However, as I’ll explain in this post, I would submit to you that this isn’t new. The trend in redistricting has been to guarantee a certain number of seats for each party in the House, leaving just the handful of truly competitive districts that we have today.

The Big Picture

Americans are increasingly frustrated with a Congress that feels out of step with the country. In fact, recent polling shows that just 35 percent of voters approve of the job that Congress is doing. However, among polled voters, 79 percent approve of elected officials who stand up to their own party, and 60 percent approve of leaders who cooperate with the opposing party.

How, then, did we get to a place where it seems like gravitating to the extremes, not to the middle, is what electeds in Congress feel they need to do to stay in office? A deeper look into how we draw the congressional districts that members represent reveals a key reason why. Redistricting, which was aimed at fairly reflecting the demographics of each state, has morphed over time into a tool for partisan entrenchment, taken advantage of by both party machines.

The U.S. Constitution, in Article I, Section 2, mandates that congressional seats be apportioned among the states based on population, with a census that is to be conducted every ten years: “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers…The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct.”

Later on, Article I, Section 4 leaves state legislatures with primary responsibility for this process: “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof, but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations.”

One can speculate that this decision to leave such a great responsibility with state legislatures was rooted in practicality, as well as out of a desire to have representation decisions made at a level as close to the people as possible. In the early republic, redistricting was a simple affair. However, it did not take long for politics to begin distorting the process.

The term “gerrymander,” used today to describe strategic redrawing of electoral districts, dates back to 1812, when Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry approved a bill that established highly contorted state senate election districts, one of which resembled the shape of a mythological salamander. What might stand out to Americans today is how relatively normal even this strange salamander shape, for which "gerrymandering" is named, looks as compared to some of the more egregious maps we see emerge from legislatures around the country today.

Source: Political Cartoon from 1812

Doubtless, this system, where politicians choose their voters rather than the other way around, is not what the founders intended. Yet, thanks to sophisticated software and detailed voter data, redistricting has become a high-tech and high-stakes activity, used by both parties to maximize control over a state and minimize opportunities for challenges and competition against them.

Zooming In

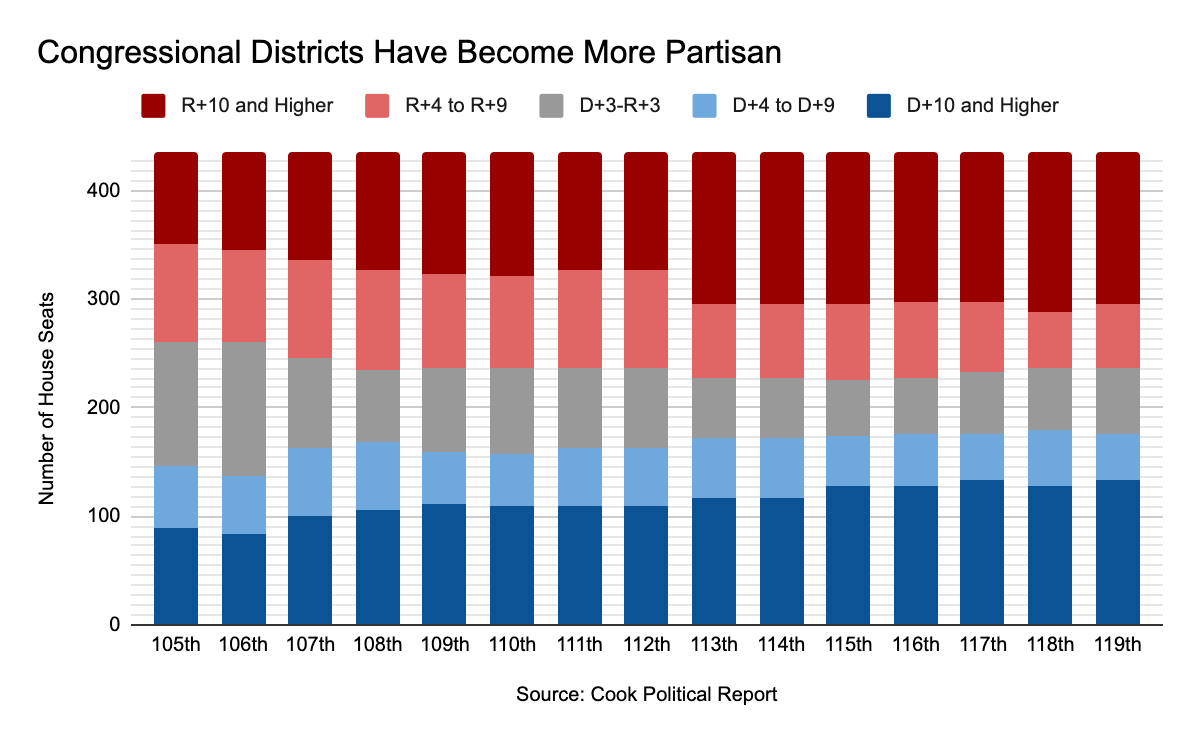

It’s worth exploring, then, what the impact of the hyper-politicization of this process has been on who is actually representing us in Washington. In 1997, during the 105th Congress, 113 House districts had a relatively balanced partisan lean (Cook PVI between D+3 and R+3), meaning they were competitive enough for either party to have a solid chance of winning. By the current 119th Congress, that number has been nearly cut in half, to 61 seats. Meanwhile, the breakdown of extremely noncompetitive seats (Cook PVI of D+10 or higher or R+10 or higher) has increased by nearly two-thirds, from 174 to 273. These seats, come general election time, are all but guaranteed to go to the party whose district maps favor it, leaving little room for those who represent more moderate opinions to have a chance at being represented.

Furthermore, cross-party representation has significantly declined during this same period, with 84 total districts being represented by the “opposite” party of their Cook PVI in the 105th Congress, down to only 10 districts fitting that same description in the 119th Congress.

This dramatic shift did not happen by accident. Partisan redistricting is driving polarization by packing like-minded voters into districts, which insulates incumbents and guts electoral accountability. The effect of this, then, is that the “real” elections become the primaries in these districts, not the general elections. In these “safe” districts, the biggest threat that an incumbent lawmaker can face is not from the other party—it is from a right-flank or left-flank challenger from within their own party, most often with more extreme views than the incumbent. That means that Democrats are pushed further left, and Republicans are pushed further right. It is with this backdrop that we have seen bipartisan cooperation and incentives for it disappear.

Take, for example, the ousting of former Rep. Joseph Crowley (D-NY) in favor of extreme leftist Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) in 2018, or further back, the ousting of then-House Majority Leader Eric Cantor (R-VA) in favor of hyperconservative former Rep. Dave Brat (R-VA) in 2014.

As a result of this shift, elected members of Congress are incentivized to protect their right or left flanks, respectively, to fend off potential primary challengers and appeal to voters within their own party only, and are no longer incentivized to legislate and make decisions in the best interest of all of those constituents that they represent that may fall outside of their party lines.

In response to this, some states have created independent or nonpartisan redistricting commissions, taking map-drawing power out of the hands of full state legislatures. States like Arizona, California, and Michigan have adopted these reforms. While some results are promising in that districts are more geographically coherent and perhaps less skewed, it is important to note that not all “independent” commissions are created equal. Some still include partisan appointees or allow legislative overrides, and other critics argue that unelected commissions take these critical decisions too far away from voter control in the process.

Other states have adopted reforms like open primaries and ranked-choice voting, which are both intended to address the downstream effects of safe seats by encouraging broader voter participation and rewarding coalition-building over partisan extremism.

Through the Lens of the Politically Homeless

As we know, most Americans don’t live on the political fringe. Voter registration and polling show a growing number of people identifying as independents, frustrated with major parties. They want functioning institutions, not grandstanding and gridlock, but the current system does much to silence the independent majority. Gerrymandered maps leave voters with fewer meaningful choices.

Redistricting was never supposed to be a partisan weapon; instead, it was meant to ensure equal voices and fair representation. Today, it is safe to say that, for the most part, it is doing the opposite, leaving the middle majority all but voiceless in the political process in Washington.

Fixing the gerrymandering problem won’t solve every problem in Congress, but it is undoubtedly a necessary step. Competitive districts produce accountable leaders who are more likely to govern with the full public’s interest in mind, not just the interests of the radical few.

I feel the need to note that California lawmakers would not be redrawing new lines if it weren’t for Texas Republicans seeking to redraw the lines in the Lone Star State to create five new Republican districts. The gaslighting from Republicans on this is truly something to behold.

Currently, there are 40 House seats rated by the Cook Political Report as “Toss Up,” “Lean Democrat,” or “Lean Republican.” This means about 9 percent of congressional seats are truly competitive. Another roughly 7 percent are “Likely Democrat” or “Likely Republican.” This means that about 84 percent of seats—366, in total—are “Solid Democrat” or “Solid Republican.”

Gallup previously provided monthly data going back to at least 2004, if memory serves. Those data really highlighted the change. I was able to find in my old files a chart with those data, but since I don’t have a source, I’m not going to include it. Unfortunately, the data made available now only goes back to the beginning of 2015.