Presidential Interference in the Federal Reserve Is a Recipe for Disaster

Nixon's pressure on the Fed before the '72 presidential election is an example from history

As you may have heard, Donald Trump has supposedly fired Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook for alleged mortgage fraud. Federal Housing Finance Agency Director Bill Pulte made the allegations against Cook, who the Senate confirmed to a 14-year term in May 2023. There was pressure on Cook to resign in advance of the supposed firing, but she refused, insisting that she had done nothing wrong. It’s essential to note that Cook hasn’t been charged with a crime.

Trump, of course, needs “cause” to remove Cook or any of the other members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve. Still, Trump’s move is the latest in his barrage of attacks against the Federal Reserve and Chairman Jerome Powell, who Trump frequently criticized for not acting to lower interest rates. Trump has a track record of urging the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates. He did the same during his first term, even when the economy performed well.

More recently, Trump has advocated for lower interest rates as a means of economic stimulus. He has cited the European Central Bank's interest rate cuts as a reason for the Federal Reserve to move forward with its own rate adjustments.1 Inflation has markedly declined in the Eurozone while economic uncertainty has increased because of Trump’s trade war. Europe is doing what it can to prepare for challenging times. Meanwhile, Trump’s trade war has created economic uncertainty in the United States and is exerting upward pressure on inflation. The Federal Reserve will respond with interest rate increases if inflation begins to rise again.

Trump is gradually working toward having a majority on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).2 If he’s successful, the FOMC will presumably be more inclined to base its decisions on what Trump wants. Trump has already nominated Stephen Miran to fill an open spot on the Board of Governors, and that nomination is expected to move quickly in September when the Senate returns. Miran is the chief architect of the so-called “Mar-a-Lago Accord.”

The idea of the Mar-a-Lago Accord is similar to the Plaza Accord signed in September 1985 by the United States, France, Japan, the United Kingdom, and West Germany. The agreement was phased out. A new agreement, the Louvre Accord, was signed by the United States, France, Japan, the United Kingdom, West Germany, and Canada. Part of the goal of the Louvre Accord was to push the dollar back up because it had fallen too far against other currencies.

The Mar-a-Lago Accord shares a similar goal to the Plaza Accord of 1985, but it incorporates additional elements. The United States would work with participating countries to weaken the dollar, while also restructuring the debt and the global trade system. Miran all but spelled this out in an April 8 speech at the Hudson Institute. The U.S. Dollar did indeed weaken since the imposition of the tariffs because tariffs reduce imports, therefore lessening the need to buy foreign currency. This would reduce the trade deficit, particularly with China. The problem is, even with a slim chance of success that most economists think it has, the Mar-a-Lago Accord would take time to implement.

The Federal Reserve making decisions based on what does or doesn’t politically benefit the administration in power inherently isn’t a good idea. Let me rephrase. It’s a terrible idea. The Federal Reserve is an independent entity that shouldn’t base its decisions on an administration’s policy or political goals.

Powell has chaired the Federal Reserve since February 2018, having been appointed by Trump. He guided the Federal Reserve through the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent inflation caused by the fiscal response to the pandemic, supply chain disruptions, rising energy prices due to global uncertainty, and strong consumer demand. Some would even argue that the Federal Reserve contributed to inflation due to its monetary policy during the pandemic, which included artificially low interest rates and quantitative easing (read: debt monetization).

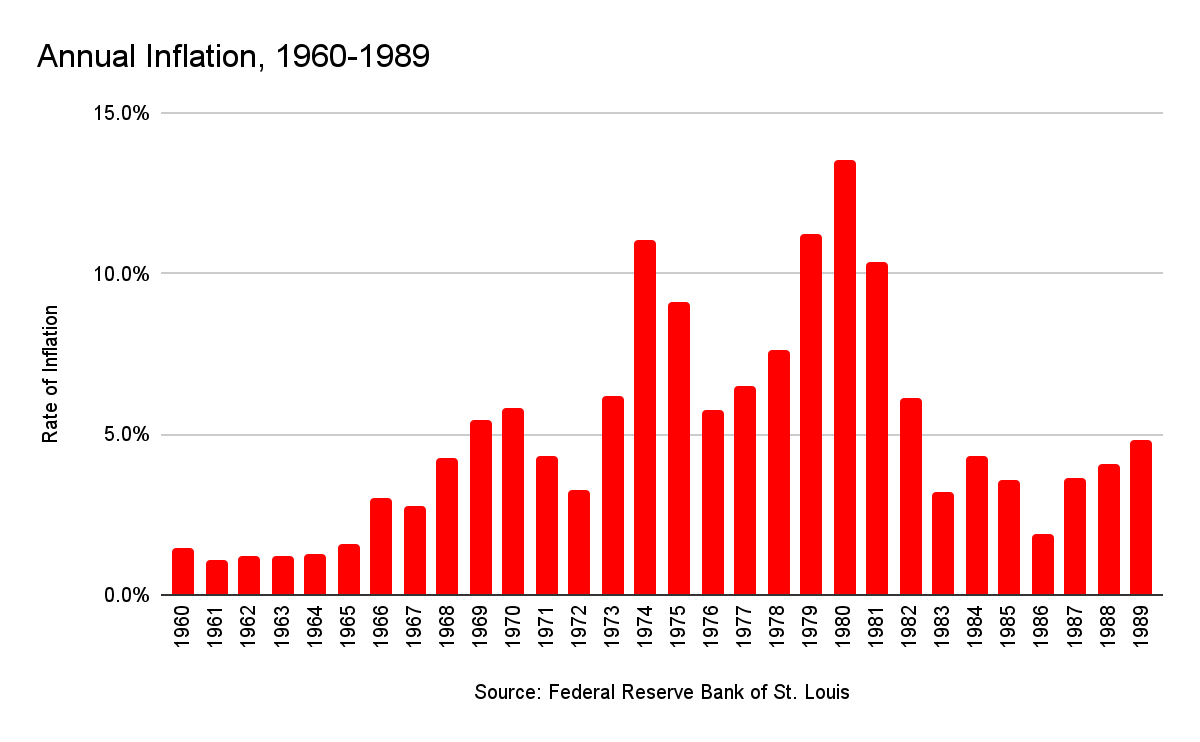

The Federal Reserve has a “dual mandate”—a target of 2 percent inflation and full employment. The success of an administration isn’t part of that mandate. We have an example of how political pressure on the Federal Reserve can lead to unfavorable economic outcomes, like inflation. President Richard Nixon pressured Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns ahead of the 1972 presidential election to keep interest rates low.3 A loose monetary policy combined with wage and price controls ushered in the era of stagflation.

As wage and price controls were lifted and the Federal Reserve increased interest rates, inflation soared from 3.3 percent in 1972 to 6.3 percent in 1973 and 11.1 percent in 1974. In context, inflation in 2019 and 2020 was below the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. It jumped to 4.7 percent in 2021 and 8 percent in 2022 before falling to 4.1 percent in 2023.

Arguably, the Federal Reserve’s decision to keep interest rates artificially low had a bigger impact on the United States than the “Nixon shock”—the effects of removing the United States from the last vestige of economic order established by Bretton Woods. The impact of the Nixon shock was more global, while the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy decisions caused domestic pain.

The Nixon and Burns example is a cautionary tale for those who support Trump’s antagonism toward Powell, Cook, and the rest of FOMC. Tying monetary policy to the success of any administration, regardless of party, would damage the credibility of the Federal Reserve in ways that could cause serious economic damage. It’s another one of those lessons we can learn from the past.

The European Central Bank has cut rates eight times since February 2024. However, there was a hint at a pause in further rate cuts in June.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) consists of 12 members, which includes the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and four of the presidents of the remaining Federal Reserve Banks around the country. Among the FOMC’s responsibilities is setting interest rates.