Russ Vought Is Living in a Fantasy World

Voters want more bipartisanship in Congress, not less

Recently, Office of Management and Budget Director Russ Vought gave a speech in which he said that the annual appropriations process “has to be less bipartisan.” He further added that “[t]here is no voter in the country that went to the polls and said, ‘I’m voting for a bipartisan appropriations process.”

As I’ve recently documented, the appropriations process has been a train wreck for quite some time. Still, even if congressional leadership and appropriators can’t get the 12 regular appropriations bills done on time, they have managed to push through omnibus spending bills in bipartisan fashion. The process is awful, of course, but there’s usually agreement on both sides of the aisle when it comes to discretionary spending.

Vought’s comments, though, are confusing. The appropriations process in the House is largely a partisan exercise. Occasionally, the House does get something in the final product, but that’s part of the give and take that comes with the process. Over in the Senate, bipartisanship is the only way to get regular appropriations bills across the finish line. That’s just a fact of life in the Senate.

The party in the majority needs 60 votes for cloture before a vote on final passage. Republicans have 53 seats. If all Republicans vote for cloture, seven Democrats have to cross party lines to vote for the procedural motion. Now, Republicans could enforce the Senate rules to consider regular appropriations, but it could take weeks just to get one bill across the finish line.

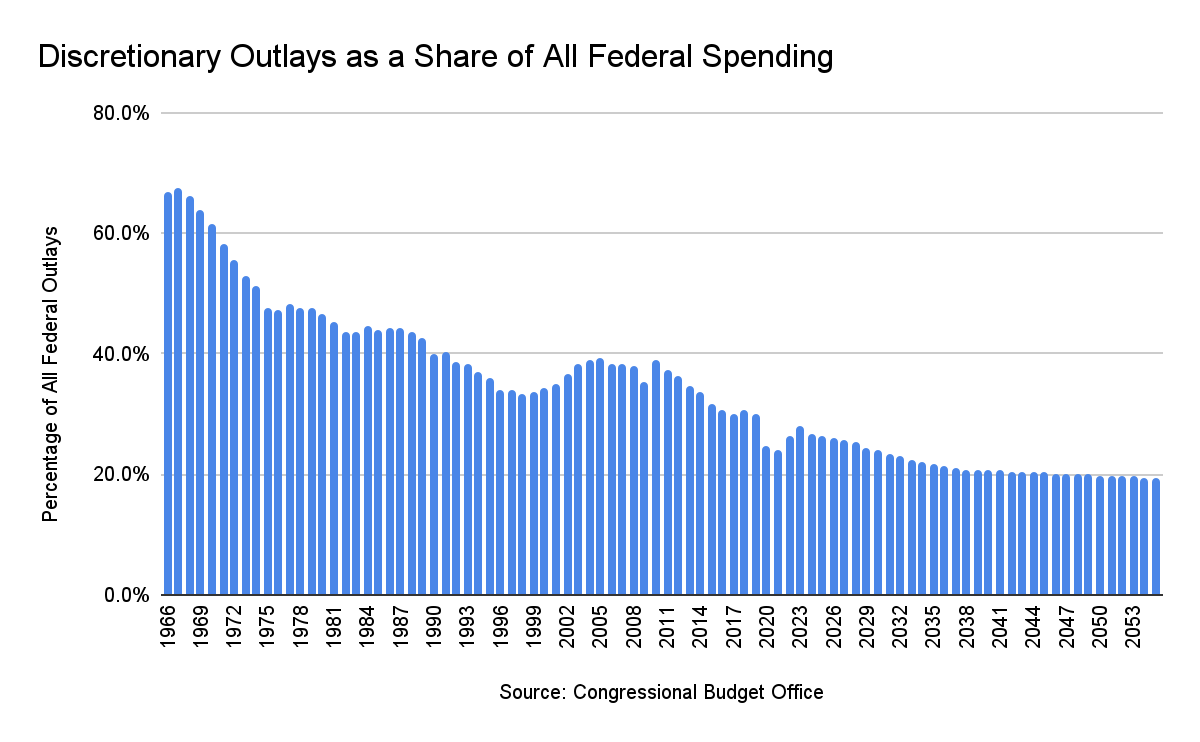

Unless Vought is endorsing eliminating the 60-vote threshold for cloture, which Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) has pledged to maintain, then he knows a “less bipartisan” appropriations process isn’t realistic, nor should it be.1 There’s also this obsession on the far right with discretionary spending that I just don’t fully understand.2 Discretionary spending, as a share of all federal spending and as a percentage of gross domestic product, has declined and is projected to continue its decline.3

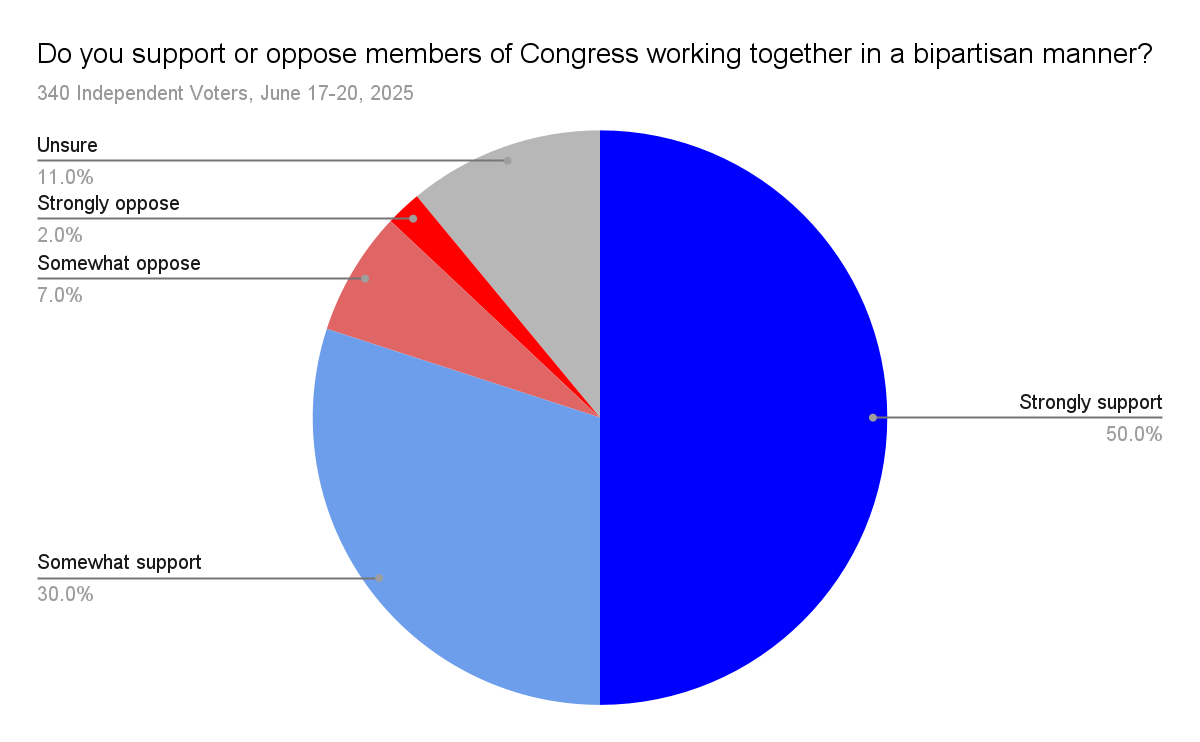

Vought’s comments expressing his belief that voters don’t care about a bipartisan appropriations process are short-sighted and misrepresent what voters want. We actually just did polling on this with the Bullfinch Group. We asked registered voters, “Do you support or oppose members of Congress working together in a bipartisan manner?” Among those voters, 78 percent want Congress to work in a bipartisan manner. Only 9 percent don’t want that.

Among independent voters, who both parties need to win elections, the numbers are even higher. Fully 80 percent of independents want Congress to work in a bipartisan manner while 9 percent don’t.

Now, the question isn’t specific. I’ll concede that much. Still, the sense of voters is that they want Congress to work across the aisle. Instead, what we’re getting is the most partisan people in both parties–particularly on the Republican side in this administration and in Congress–making it very difficult for any sort of bipartisan agreement. Vought–and by extension, Trump and congressional Republican leadership–aren’t doing themselves any favors. No party can govern for only its base. Regardless of which party is in power, independent voters will be the correction in the next election.

Vought is, of course, a Christian nationalist. Perhaps he should read Matthew 16:26, in which Jesus of Nazareth said, “What good will it be for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul? Or what can anyone give in exchange for their soul?” To put a modern twist on this for the current predicament of Vought and Republicans, what good will it be for Republicans to gain all of MAGA, yet forfeit independent voters increasingly weary of partisanship? The allure of short-term power, I guess, matters much more. Let’s be honest. That’s what this is all about, anyway.

Legistorm shows that Vought got his start in Washington, DC in the Senate. He worked for Sens. Phil Gramm (R-TX) and Chuck Hagel (R-NE) for approximately four years in total before moving over to the House from early 2003 until mid-2010. He knows how the Senate works.

Vought has focused much of his efforts on reducing outlays on “woke spending.” These days, anything can be considered woke, and even if Congress eliminated such spending, it wouldn’t do much to reduce the budget deficit.

This isn’t to say that discretionary spending doesn’t matter. I’ve been accused of suggesting that. Of course, discretionary spending matters, but it’s not what’s driving budget deficits and debt. What drives deficits and debt is mandatory outlays and spending on net interest, primarily on the share of the debt held by the public.