The Federal Budget Deficit Was $1.8 Trillion in FY 2025

Programs and categories of spending driving deficits and debt continue to grow

Well, the numbers for FY 2025 are in, and the federal government ran a budget deficit of approximately $1.8 trillion. There’s a bit of a discrepancy between the Bureau of the Fiscal Service and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). The Bureau of the Fiscal Service reports a budget deficit of $1.775 trillion in FY 2025. The CBO estimates the budget deficit at $1.809 trillion. I’m not sure why there’s a discrepancy of $34 billion.

The data are interesting for a few different reasons.

There has been a big focus on spending since January. Obviously, Elon Musk was the face of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE). According to DOGE’s website, this effort has supposedly saved $214 billion. Contract cancellations and grant terminations are approximately $110 billion of the purported savings. Yet, outlays grew in FY 2025 compared to FY 2024 by $250 billion to $259 billion, depending on which agency’s numbers you’re looking at.

Although the concept of DOGE was a good one,1 it clearly failed to live up to the expectations communicated. It was too politicized. There wasn’t much of an attempt to build any sort of bipartisan coalition around DOGE. DOGE’s headcount strategy failed because it equated fewer employees with greater efficiency.2 By using staff reduction as the main measure of success, DOGE ignored productivity, institutional knowledge, and mission performance. The cuts produced short-term savings but long-term costs—undermining service capacity, morale, and oversight. Rather than reforming processes or improving outcomes, the initiative treated headcount as an end in itself, weakening the very institutions it was meant to streamline.

Congress only enacted one rescissions package—the Rescissions Act, H.R. 4—which canceled nearly $9.4 billion in budget authority, about 89 percent of which was for FY 2025. The actual outlays canceled for FY 2025 were $316 million. Roughly 83 percent of the outlays related to that spending were to be spent from FY 2026 through FY 2029.3 Although the Office of Management and Budget used a constitutionally problematic theory known as “pocket rescissions” to withhold some spending, Congress is likely to continue funding those very same programs in FY 2026, either through a continuing resolution (CR) or an appropriations package.4

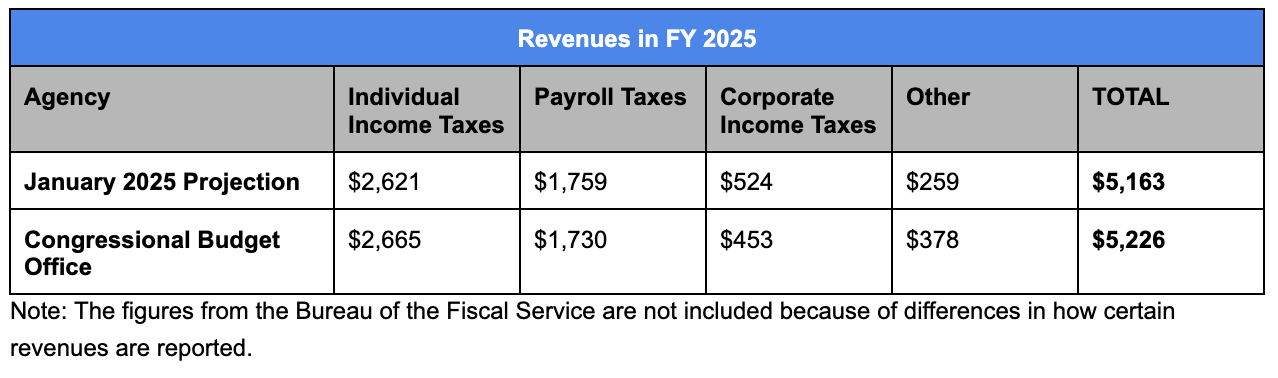

According to the Bureau of the Fiscal Service and the CBO, the federal government collected $63 billion more in revenue than the CBO projected at the beginning of the year. Individual income tax receipts were up slightly compared to the baseline projection while payroll taxes and corporate income taxes were below the projection. What’s labeled as “Other” includes customs duties.

The Bureau of the Fiscal Service notes that customs duties were estimated at $63 billion in FY 2025. Obviously, the 10 percent global tariffs and the more significant tariffs against specific nations have resulted in a substantial increase in customs duties revenues. Total customs duty collections in FY 2025 are $195 billion. That’s $132 billion over the projection. One reason that’s notable is because, had customs duties come in at the projection, the budget deficit would’ve been $1.941 trillion. Had they come in at the same level as in FY 2024 ($77 billion), the deficit would’ve been $1.927 trillion. Both figures are much higher than the budget deficit of $1.865 trillion projected by the CBO in January.

We need to wait a little longer, probably some point in January or February, to get a better sense of short- and medium-term deficit projections. Of course, the budgetary effects of the so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” will be included in those projections. Larger customs duty revenues should also be included in those projections.

Finally, the outlays for the five largest categories or programs grew by $412 billion compared to FY 2024. Spending for four of these programs—Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and net interest on the share of the debt held by the public—is based on obligations. Congress doesn’t appropriate funding for these programs. The only one that falls into the discretionary category—and, thus, subject to appropriation by Congress—is defense spending.

Even with menial cuts elsewhere,5 federal outlays still grew by $250 billion to $259 billion. It’s growing because the Trump administration and congressional Republicans aren’t focusing much at all on the drivers of deficits and debt. Sure, Congress did include some changes to Medicaid that may reduce future outlays for that program. That’s only if those changes survive political tests that come from changes in congressional power. Regardless, the reductions from the changes to Medicaid are a drop in the bucket.

The notion of modernizing government agencies and systems with the goal of making them more efficient is important and not something anyone should oppose. However, DOGE ended up being partisan and significantly less focused on streamlining government.

Headcount refers to the total number of employees or positions within an agency. It’s often used as a simple measure of workforce size and cost, but it doesn’t reflect productivity, performance, or mission needs.

The so-called “pocket rescissions”—spending unconstitutionally withheld by the administration—don’t reduce budget authority.

Honestly, I have no idea what to expect right now. There’s a preference for an appropriations package or packages, but a CR, either whole or partial, is possible.

I’m not saying these spending cuts are “bad,” but the reductions are small in the grand scheme of federal budgeting. Of course, Congress has to approve spending cuts and the termination of something like the Department of Education, etc. That’s the way the Constitution works. The precedent being set is horrible, and I wish conservatives would see that.