Executive Power, Pocket Rescissions, and the Impoundment Control Act

The power claimed by Trump and his administration is beyond scope of Article II

The fiscal year ends at the end of September. What happens between when the House and the Senate return on September 2 and September 30 is anyone’s guess. The assumption for those of us who follow appropriations had been that Congress would pass a continuing resolution (CR) to some point in December. This way, appropriators in the House and the Senate could work on a full-year government funding package. That’s still a possibility, but the likelihood of a government shutdown appears to be growing due to several factors.

Two primary issues are coming to a head.1 The first is the power that the administration has claimed over how money allocated by Congress is spent. The second is the administration’s recent use of federal agents and the National Guard in the District of Columbia and the threats to do the same in other Democratic cities. For our purposes, we’re going to focus on the first one.

One of the notable aspects of Congress's consideration of the CR that funded the federal government for FY 2025 was the number of moderate to center-left Democrats who opposed it.2 Take, for instance, Sen. Jon Ossoff (D-GA). The first-termer, who is in cycle in 2026, voted against the CR, in part because of the lack of checks and balances from Congress. “The House bill also irresponsibly fails to impose any constraints on the reckless and out-of-control Trump Administration. The Administration is gutting the CDC and the VA while destabilizing the economy,” said Ossoff in a press release. “Both parties in Congress must fulfill our Constitutional obligation to check the President.”

Sen. Elissa Slotkin (D-MI), who entered the chamber earlier this year after winning a close race, cited the administration’s lawlessness around appropriations. “[M]y Republican colleagues offered no assurances that the money wouldn’t just be redirected at the whim of Elon Musk,” said Slotkin. “They offered no assurances that the Trump Administration would follow the law.”

Some might say, “Well, Trump did send a rescissions package to Congress, and it was passed.” That’s true. The Rescission Act, H.R. 4, became law in July. The rescissions package reduces outlays, according to the Congressional Budget Office, by $9.3 billion through FY 2035.3 Like it or not, the approach is consistent with the law. Additional rescissions packages had been discussed, but it seems unlikely that the White House will submit another one.

Instead, Trump’s top budget official, Russ Vought,4 plans to pursue an unlawful strategy of simply running out the clock on FY 2025 so he doesn’t have to disburse money appropriated by Congress and signed into law. This practice has been dubbed “pocket rescissions.”5 I say that pocket rescissions are unlawful for two reasons.

First, the Constitution gives Congress control of spending in two places. Article I, Section 8, Clause 1 states, “The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States.” Article I, Section 9, Clause 7 is more direct, reading, “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time.”

Congress determines where the money gets spent. The president has the opportunity to speak on funding when the bill is presented for approval or veto. If the president signs the appropriations bill into law, the expectation is that the administration will carry out the will of Congress. This is how it’s supposed to work. Congress can rescind money for obligation through the Impoundment Control Act, as was done through the Rescissions Act.

Second, so-called “pocket rescissions” are unlawful because such actions violate the Impoundment Control Act (ICA). The Government Accountability Office issued an opinion on “pocket rescissions” in December 2018, specifically highlighting the ICA as it relates to appropriations.

“The Constitution vests in Congress the power of the purse, and Congress did not cede this important power through the ICA,” GAO explained. “Instead, the terms of the ICA are strictly limited. The ICA permits only the temporary withholding of budget authority and provides that unless Congress rescinds the amounts at issue, they must be made available for obligation. The President cannot rely on the authority in the ICA to withhold amounts from obligation, while simultaneously disregarding the ICA's limitations.”

The problem today is that Vought contends that the ICA is unconstitutional. In September 2024, Vought’s former organization published a piece coauthored by Mark Paloetta, who is now the general counsel for the Office of Management and Budget, claiming that the president has the authority to impound money appropriated by Congress under Article II of the Constitution. Specifically, Paloetta and his coauthor, Daniel Shapiro, claimed that this power comes from four different clauses of Article II—the Executive Vesting Clause, the Take Care Clause, the Commander-in-Chief Clause, and the Foreign Affairs and Reception Clause.

Paoletta argues that the Impoundment Control Act took a power away from the Executive Branch that had existed since the Constitution came into being. “From at least the Jefferson Administration, Presidents have robustly employed impoundment for reasons ranging from foreign affairs, Executive Branch management, good governance, economy and efficiency, policy, and much else. This practice was acknowledged as executive in nature and applauded by legislators. Any attempt to question it was quickly rebutted by legislative majorities.”6

One of the problems with the approach that Paoletta and Shapiro take here is that, as the Congressional Research Service (CRS) explains, “Presidents typically sought accommodation rather than confrontation with Congress.” As the United States went deeper into the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s, and defense funds were aplenty, there were disagreements between presidents and Congress on impoundment. Despite the disagreements, CRS notes, “While some impoundments during these periods were motivated by policy concerns, they typically involved temporary spending delays, with the President acting in consultation with congressional leaders, so that a protracted confrontation between the branches was avoided.”

In other words, impoundments were less about a power grab, unlike today, and presidents worked with Congress to address concerns. That changed as the power of impoundment was abused, notably by Richard Nixon. In 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act,7 which made federal money available to states and local jurisdictions for certain projects. Nixon directed the head of the Environmental Protection Agency, Russell Train, not to make all the dollars allocated available. Train did as directed. The City of New York sued.8 Eventually, the case, Train v. City of New York, made its way to the Supreme Court in November 1974.

The Court unanimously held that the Clean Water Act did not provide the authority to Train to withhold all the money available. However, the Court’s decision was only about the authority to impound funds made available by the Clean Water Act. The opinion also had nothing to do with the ICA. Although the ICA became law in July 1974, the Court did not believe the case had become moot.

Later, in Clinton v. City of New York (1998), the Court held that the Line Item Veto Act of 1996 was unconstitutional because it violated the Presentment Clause of the Constitution. In the majority opinion, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote, “Although the Constitution expressly authorizes the President to play a role in the process of enacting statutes, it is silent on the subject of unilateral Presidential action that either repeals or amends parts of duly enacted statutes.”9

“There are powerful reasons for construing constitutional silence on this profoundly important issue as equivalent to an express prohibition. The procedures governing the enactment of statutes set forth in the text of Article I were the product of the great debates and compromises that produced the Constitution itself. Familiar historical materials provide abundant support for the conclusion that the power to enact statutes may only ‘be exercised in accord with a single, finely wrought and exhaustively considered, procedure,’” Stevens added.10

Although Justice Antonin Scalia dissented in part, he briefly touched on Train. Now, I would be remiss if I didn’t note that Scalia acknowledged that presidents have traditionally been given some discretion over appropriations. Granted, every single instance he cited, though, came before the enactment of the Impoundment Control Act. He’s referencing the discretion provided before Congress limited it through the ICA.

Scalia wrote, “President Nixon, the Mahatma Gandhi of all impounders, asserted at a press conference in 1973 that his ‘constitutional right’ to impound appropriated funds was ‘absolutely clear.’ Our decision two years later in Train v. City of New York proved him wrong, but it implicitly confirmed that Congress may confer discretion upon the Executive to withhold appropriated funds, even funds appropriated for a specific purpose…This Court held, as a matter of statutory interpretation, that the statute did not grant the Executive discretion to withhold the funds, but required allotment of the full amount authorized.”

Court precedent isn’t on the side of Trump, Vought, and Paoletta. The gamble that this trio is making is that the Roberts Court will view the scope of executive power differently. Thus far, the Court has had a proclivity to side with the Executive Branch. However, the constitutional principles in the discussion aren’t at all vague. The Constitution gives Congress the power to make appropriations. The supposed executive power to impound funds doesn’t textually exist,11 and the traditional power that presidents had to impound funds has been limited.

The Impoundment Control Act and Limitations on Executive Power

So, what’s the Impoundment Control Act?12 The Impoundment Control Act was passed in 1974 in response to Nixon’s abuse of the traditional power of the Executive Branch to impound funding.13 After all, as Scalia noted in Clinton v. City of New York, Nixon was “the Mahatma Gandhi of all impounders.” He used impoundment to withhold funding for domestic programs.

The Impoundment Control Act simply provides a mechanism for a president to defer or impound funds appropriated by Congress.14 Although a president’s ability to defer funding is notable, the most relevant aspect of the law is how impoundments are handled. If there’s disagreement with Congress’s funding priorities, a president may send a special message to Congress and the Comptroller General,15 seeking the rescission of part or all of the budget authority from that obligation.16 The message must also be published in the Federal Register.

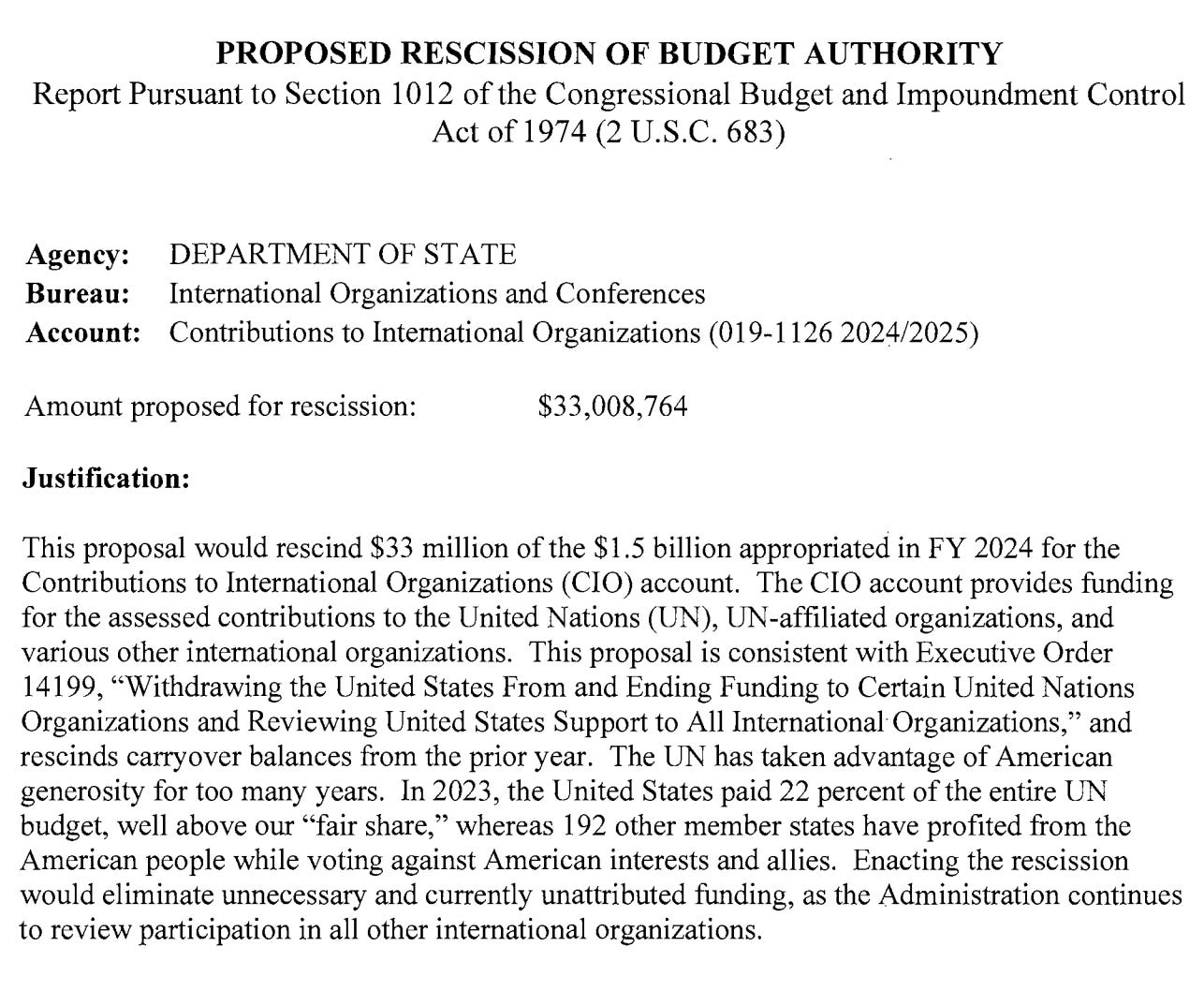

The message must include the amount of budget authority the White House is requesting Congress to rescind, the account for which the budget authority was allocated, and the justification for the request. You can view the message from the White House regarding the Rescissions Act here (or here) or see an example of one of the proposed rescissions below.

The mere fact that the White House is seeking the rescission of funds doesn’t mean much unless Congress acts. If Congress takes no action on the rescissions request or otherwise fails to pass it, the ICA requires that the funds still be made available for obligation after 45 calendar days of continuous session.17 In other words, the funding has to be released and can be spent. The 45-day clock starts on the day Congress receives the message.

Now, the actual process for passing proposed rescissions is privileged in the Senate. The typical Rule XXII procedure requiring three-fifths for cloture doesn’t apply. If the House or Senate committee to which the rescissions bill has been referred sits on the bill in an attempt to kill it, the ICA includes a motion to discharge the bill from committee after 25 calendar days.

The Comptroller General is basically the referee. If the president doesn’t comply with the ICA, the law allows the Comptroller General to bring a civil action against any federal official or entity to make the budget authority available. The GAO has identified at least four instances of noncompliance with the ICA by the current administration, by unlawfully withholding funds for electric vehicle chargers, the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Head Start, and the Renew America's Schools Program. This is likely one of the primary reasons why House Republicans proposed gutting the appropriation for the GAO in the Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for FY 2026.

The question of whether the ICA is constitutional or not really comes down to whether or not you believe Congress can limit the power of the president. Trump, Vought, Paoletta, and others who subscribe to the view of the imperial presidency appear to believe that executive power has no real limitations and that Congress and federal courts are subservient branches of government rather than coequal branches.18

As a matter of constitutional principles, the notion that any president and the Executive Branch are above the other branches of government is belied by the text of the Constitution. It’s also wrong as a matter of practice. Congress has acted in the past to restrain executive power, and the Court has affirmed that practice.19

Obviously, this is a perilous path because it all but obliterates the constitutional principles of separation of powers and checks and balances. We’ve also seen what the growth of the power of leaders of other countries leads to democratic backsliding. I would argue that we’re already experiencing that in the United States, and I’m concerned it’s going to get worse.

I mean, there may be more issues that others mention. I’m not saying those aren’t valid. I’m simply noting that these are the two primary issues from what I’ve observed.

A friend and colleague made the argument to me after I downplayed the fiscal impact of the rescissions package that I need to think about it differently. The Rescissions Act, he argued, guts the budget authority for agencies to make obligations of $9.4 trillion in FY 2025. Because the Rescissions Act eliminated the budget authority, it won’t come back in future fiscal years, so it’s really $94 billion. I suppose one can look at it that way, but it’s a fairly simplistic approach, and it overlooks the likelihood that a future Congress will restore these cuts. I’ve never been known for being optimistic, folks. Additionally, I don’t get overly excited about cuts to discretionary outlays, although I’m not saying that cuts shouldn’t be made.

Remember, Vought wants the appropriations process to be less bipartisan, and he’s doing everything he can to make that happen.

This is similar to a “pocket veto.” Article I, Section 7 of the Constitution states, “If any Bill shall not be returned by the President within ten days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the same shall be a Law, in like manner as if he had signed it, unless the Congress by their Adjournment prevent its return, in which case it shall not be a Law.” The difference is that the pocket veto has an actual constitutional basis. The so-called “pocket rescission” does not.

Paoletta and Shapiro separately authored a paper examining impoundments before the ICA. I’m not debating or defending the history of impoundment before the ICA became law. I’m also not willing to take any of the examples they claim at face value because the language of an appropriations bill may provide at least some deference to the Executive Branch.

Technically, the law was the Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments, but virtually everyone knows it as the Clean Water Act. Nixon vetoed the legislation, but Congress overrode the veto.

New York wasn’t the only city to sue. There was also another case deriving from the Fourth Circuit, Train v. Campaign Clean Water, Inc.

Let me stop the groans before they begin. Stevens wrote the opinion, but he was joined by Chief Justice William Reinquist and Justices Clarence Thomas (in full) and Antonin Scalia (in part).

The quote within the quote comes from INS v. Chadha (1983), in which the Court held that a one-house legislative veto violates the Presentment Clause. The case is also notable because the Court reaffirmed that Congress can place limitations on the president.

By which I mean that the Constitution doesn’t provide an explicit power to the president to impound funds. Supporters of the traditional practice of impoundment essentially argue that the power is implied. The argument also creates a conflict between Article I and Article II.

Part of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974.

By this point, Nixon was also significantly politically weakened by the Watergate scandal. The impeachment process was already underway in the House Judiciary Committee. He signed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act into law less than a month before he resigned from office in disgrace.

The Impoundment Control Act can be found in statute at 2 U.S.C §§681-688.

The Comptroller General runs the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Since I’ve used the term “budget authority” several times now, I should probably briefly explain the difference between it and an outlay. Budget authority is the legal authority that an agency has to make obligations. An outlay is the actual expenditure of dollars. This is why there’s a different between the budget authority for the Rescissions Act and the outlays. It’s not a huge difference, but that’s the explanation for it.

See subsection (b) at the link.

The common name for this is the “unitary executive theory.”

There are at least four cases that I’m aware of regarding this: Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952), INS v. Chadha (1983), Clinton v. City of New York (1998), and Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006). Without getting into each of these cases, Youngstown was about President Harry Truman’s seizure of steel plants. The Truman administration claimed substantial power under Article II—including implied powers—to seize the steel plants, but the Court disagreed. In the majority opinion, Justice Hugo Black wrote, “Instead of giving him even limited powers, Congress, in 1947, deemed it wise to require the President, upon failure of attempts to reach a voluntary settlement, to report to Congress if he deemed the power of seizure a needed shot for his locker. The President could not ignore the specific limitations of prior seizure statutes. No more could he act in disregard of the limitation put upon seizure by the 1947 Act.” Justice Robert Jackson also penned a concurrence in which he put executive power into three categories, the first category—power granted by Congress—being the most legitimate. The second category relates specifically to independent powers. However, Jackson explained, “[T]here is a zone of twilight in which he and Congress may have concurrent authority, or in which its distribution is uncertain. Therefore, congressional inertia, indifference or quiescence may sometimes, at least, as a practical matter, enable, if not invite, measures on independent presidential responsibility.” In this case, Congress has express power to appropriate funds under Article I, Section 9. There’s not even an implied power in Article II that allows a president to impose his will on appropriations, except, of course, the veto power. The least legitimate power is when a president ignores “the expressed or implied will of Congress.” Jackson wrote, “Courts can sustain exclusive presidential control in such a case only by disabling the Congress from acting upon the subject. Presidential claim to a power at once so conclusive and preclusive must be scrutinized with caution, for what is at stake is the equilibrium established by our constitutional system.”