Why Trump Is Focusing More on His International Agenda Instead of Domestic Policy

Trump’s foreign policy obsession and the incentives Congress created

The opening days of the nascent year have been dominated by the Trump administration’s quick action to depose Venezuelan authoritarian president Nicolás Maduro. The military buildup in the Caribbean off the coast of the South American nation wasn’t surprising. After months of blowing up boats that the administration claims were allegedly carrying narcotics, the operation to capture Maduro in the early hours of January 3 was the logical crescendo.

The administration has also threatened military action against Iran, Cuba, and Mexico while simultaneously jeopardizing relationships with European allies by continuing to float the idea of annexing Greenland. This posture is striking given that Trump campaigned explicitly against regime change, nation-building, and foreign military entanglements. Foreign interventionism — especially the kind that seeks to coerce or remove foreign governments — was derided as “neoconservatism,” and rejected as incompatible with “America First.” Not only that, but Trump has justified the action in Venezuela, in part, to gain access to the nation’s vast oil reserves and is floating the idea of subsidizing American oil companies that invest in Venezuela.

Here we are, watching the president engage in and threaten exactly that kind of interventionist foreign policy—a military intervention for oil, no less—now repackaged under a different political brand. It’s also problematic in a constitutional sense,1 but that’s a topic for another day.

Before resigning from the House, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) complained that Trump was too focused on foreign affairs. She wasn’t wrong. That’s not to say the United States shouldn’t lead in world affairs; it should. But why has Trump focused so much on foreign affairs? The best guess is the general normalization between Israel and many Middle Eastern countries that was initially brokered under the first Trump Administration. This includes the Abraham Accords—a set of agreements to normalize relations between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan. These agreements have been tested because of the humanitarian crisis in Gaza. Plus, Trump is obsessed with the Nobel Peace Prize, and he thinks brokering agreements around the world will get him there.

There are other equally reasonable explanations for why Trump has focused so much on foreign policy. Congress has ceded an enormous amount of power to the Executive Branch over trade, sanctions, military deployments, diplomacy, arms sales to other nations, and immigration. Some of the laws that handed the Executive Branch these powers have mechanisms for Congress to overturn an administration’s policies. Unfortunately, those mechanisms—such as joint resolutions of disapproval—are rarely used successfully. In other words, Trump doesn’t need Congress, and Congress has shown few signs of being willing to challenge him.

Plus, the negotiations that take place in foreign policy discussions fit Trump’s brand as a “dealmaker.” Brokering deals between two nations, with Trump or his envoy(s) serving as mediator, generally sidelines Congress. He doesn’t need the Senate unless he’s negotiating a treaty.2 Sure, some members may complain about a particular deal, but there’s little they can do to stop him unless there are veto-proof majorities in both chambers. It’s also true to Trump’s brand that dealmaking on the foreign policy stage is nearly always transactional. He’ll want to take a win, seemingly, however he can get it. After all, he’s tried to give Ukraine up multiple times by giving Russia nearly everything it wants. And he’s almost certainly trying to make his efforts on foreign policy a legacy piece. In addition to the vanity of Trump’s quest for a Nobel Peace Prize, winning the award would legitimize his foreign policy work and, in his eyes, legitimize his presidency on the world stage.

Still, Trump’s focus on foreign policy has come at the expense of domestic policy. In many ways, the pain Americans feel is a result of his policies. Those policies—such as trade—explain the significant drop in Trump’s approval rating. I’m a believer in the notion that the days of presidents seeing high approval ratings are over, at least for now. President Obama left office with an approval rating as high as 62 percent in some polls.3 That’s unlikely to happen again as long as we stay in this era of hyper-partisan politics.

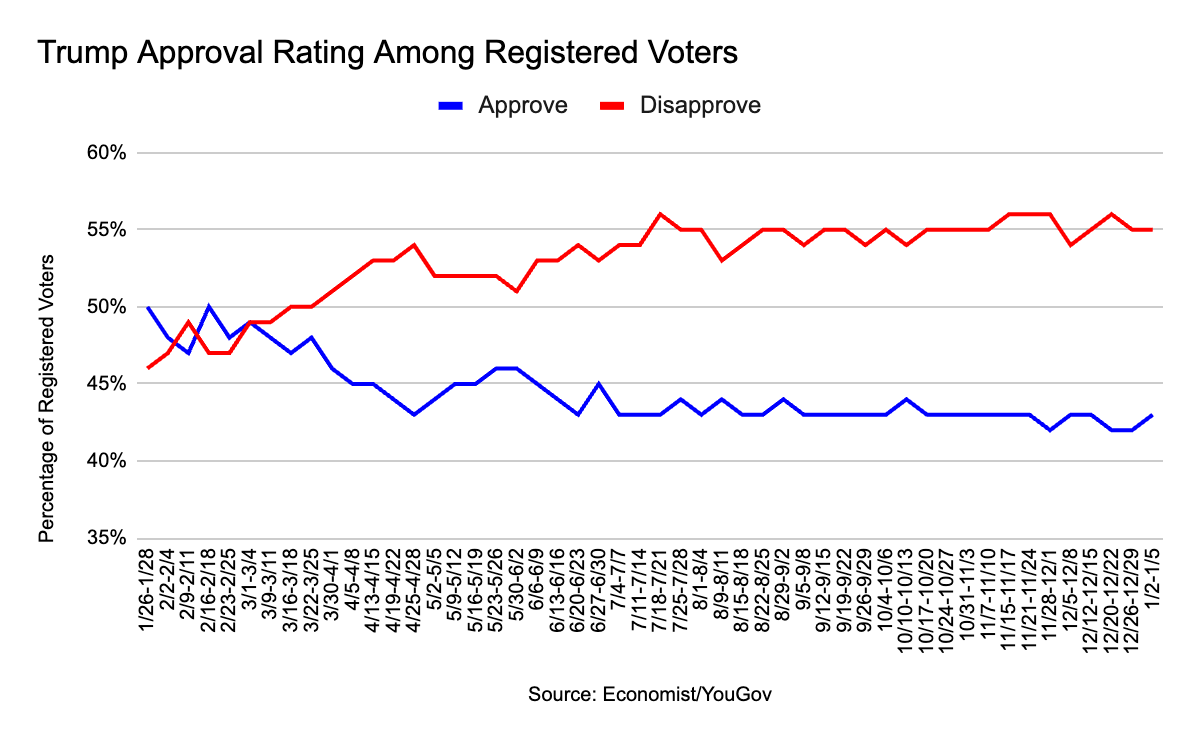

In keeping with my preference for the weekly tracking poll put out by The Economist and YouGov, let’s look at where Trump was with registered voters a year ago. Trump came into office with a 50 percent approval rating. Granted, 46 percent disapproved. Disapproval of Trump’s job performance reached 50 percent in mid-March and continued to slide. The data show that Trump bottomed out at 56 percent disapproval, most recently in the survey conducted from December 20 to December 22. According to the latest Economist/YouGov survey released on Tuesday, 43 percent of voters approve of Trump’s job performance while 55 percent disapprove.

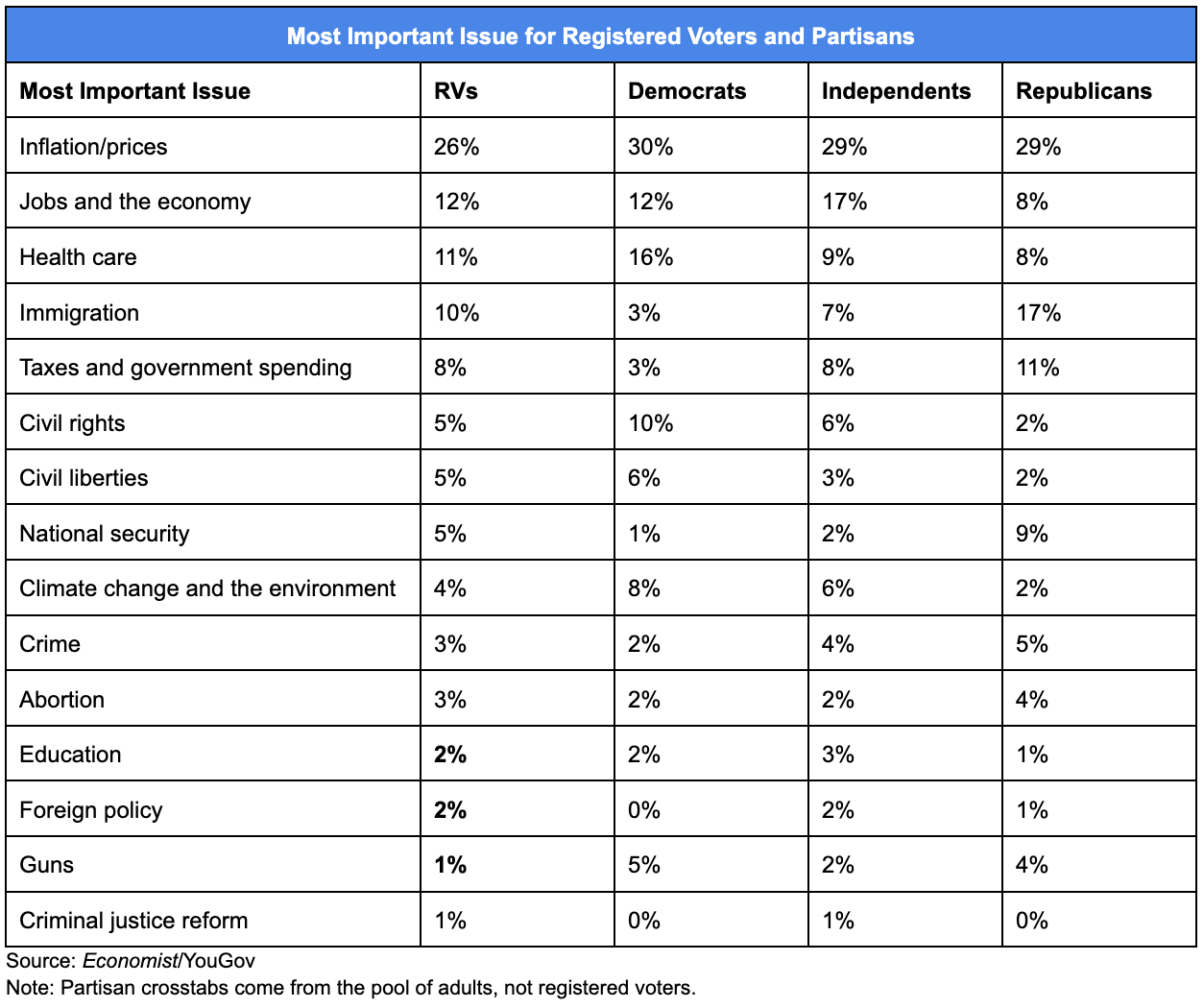

Generally, voters have prioritized three issues: inflation/prices, jobs and the economy, and healthcare. These issues were fairly consistently the top issues throughout 2024.4 In January 2025, a combined 42 percent of voters named these three issues the most important. As of the survey released on Tuesday, it’s now 49 percent.

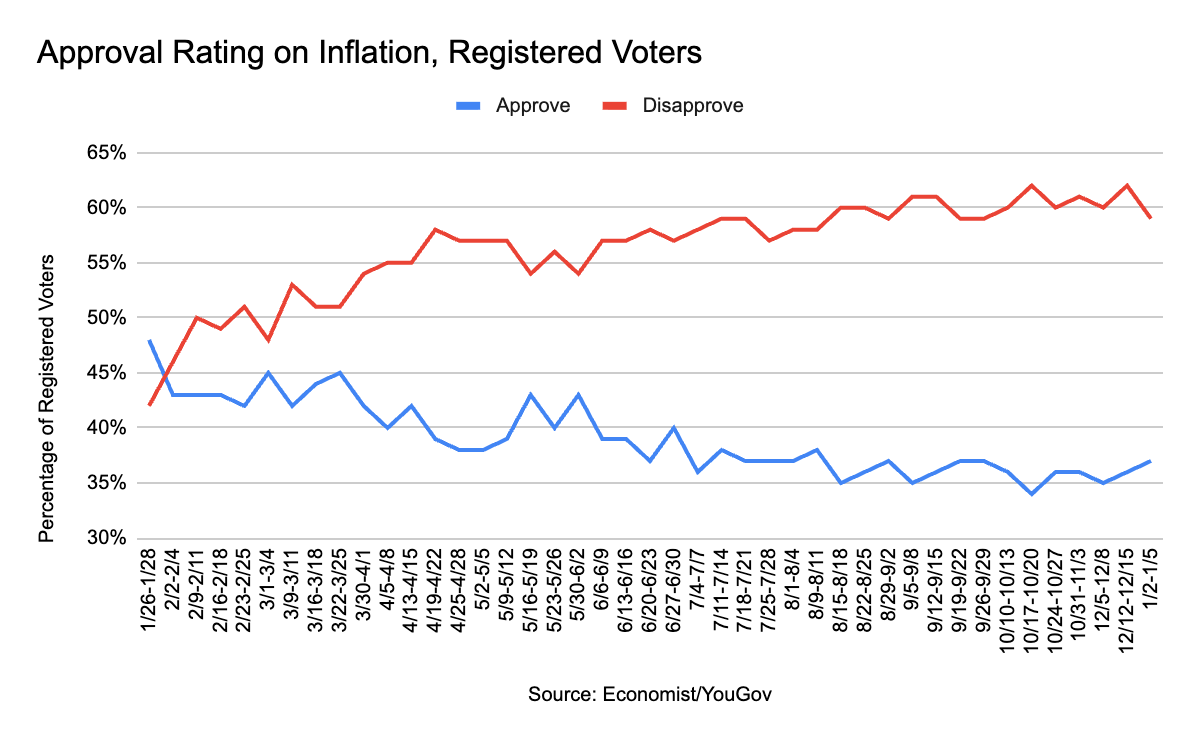

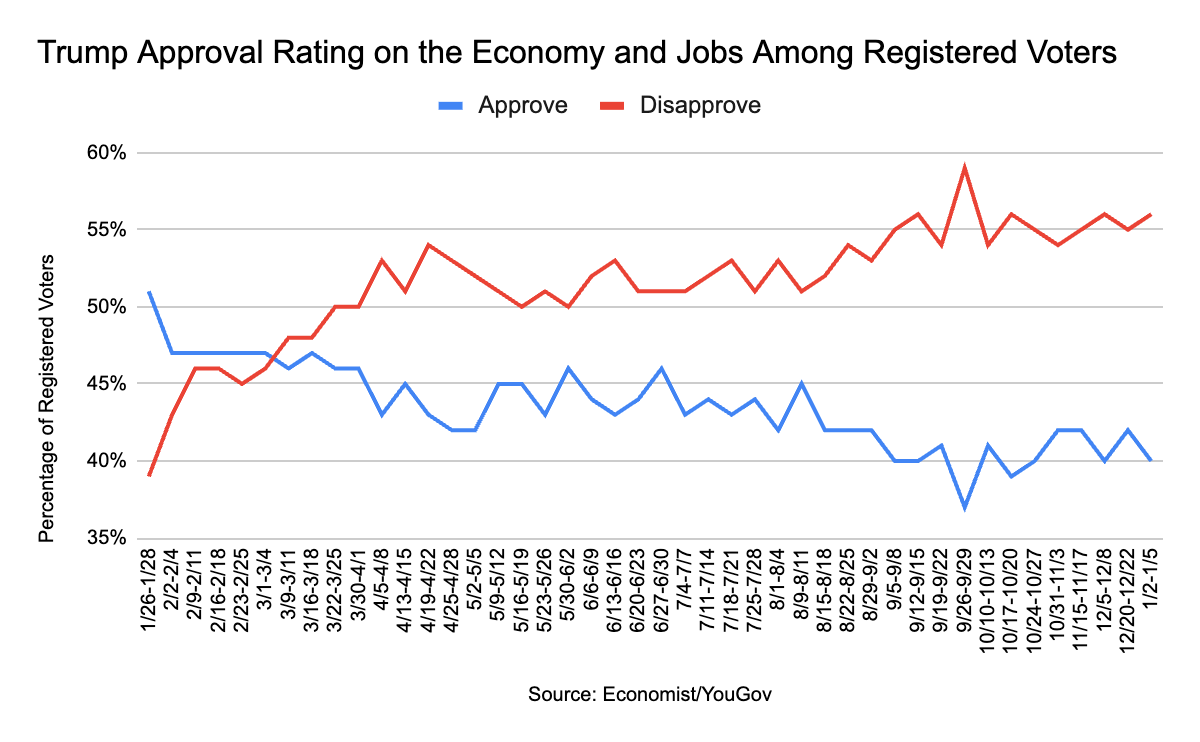

Trump’s approval rating on inflation and jobs and the economy are worse than his overall job approval. There has been some improvement, though. Trump’s approval rating on inflation fell to 34 percent in mid-October. His approval rating on jobs and the economy dipped to 37 percent in late September. He’s at 37 percent and 40 percent as of the latest survey.

Adding to Trump’s problems is that moving anything legislatively for his domestic agenda is getting much, much harder. Election-year politics effectively means that little meaningful legislating will happen after Congress returns from the August recess. The party divisions in the House also make it hard to legislate. I’ve already explained how nearly 20 House Republicans are seeking another office in 2026. That means there will be attendance problems some weeks as these members, many of whom are in competitive races, campaign back in their states. Adding to those problems is Greene’s resignation and the sudden death of Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-CA).

Although a March 10 special election has been called in Georgia’s 10th Congressional District, a runoff, likely in early to mid-April, may be needed to determine the winner.5 Gov. Gavin Newsom (D-CA) hasn’t yet called the special election in California’s 1st Congressional District.6 Newsom could get creative, much like his Republican counterpart in Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott, did with Texas’s 18th Congressional District.7 There are always other attendance issues.8

Technically, Republicans have 218 seats in the House right now. Democrats have 213 seats. The special election in TX-18 will go to Democrats. The only question is which Democrat wins, Christian Menefee or Amanda Edwards. That brings Democrats to 214. Now, the special election in GA-14 may be over by the time the special election in New Jersey’s 11th Congressional District is decided. Let’s assume it is. GA-14 goes Republican, no question. NJ-11 is very likely to stay blue. By April 11, Republicans will most likely have a 219 to 215 advantage. CA-01 may continue to dangle out there, depending on when Newsom schedules the special election. Obviously, the numbers could change if members like Reps. Don Bacon (R-NE), Elsie Stefanik (R-NY), and/or another member or members decide to peace out early and resign.

Because redistricting has largely been a wash, moderates in the House Republican Conference have a lot of power that they’re starting to use. As much as conservative members adore Trump and rank-and-file members fear him, he’s a weight on members moderates in competitive seats. We’ve already seen four of them break from Trump and House Republican leadership by signing a discharge petition to force a vote on a three-year extension of the enhanced premium tax credits.9

Trump’s turn to foreign policy isn’t a sign of strategic vision; it’s an adaptation to political constraint. With a razor-thin House majority, shrinking attendance, empowered moderates, and a domestic agenda that can be stalled by four members, governing at home is hard. Pushing an international agenda is not. Foreign policy offers Trump unilateralism, speed, spectacle, and insulation from Congress, which is exactly what the domestic arena no longer provides him. Trump can’t get what he wants through Congress, and he knows it. The danger isn’t just that presidents escape to foreign policy when legislating gets difficult. It’s that Congress, by tolerating that escape, quietly agrees to become irrelevant. If lawmakers don’t like being sidelined, they’ll have to stop acting like spectators and start acting like a coequal branch again.

The most obvious problem is constitutional. Article I, Section 8 states, “The Congress shall have Power…[t]o declare War, grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal, and make Rules concerning Captures on Land and Water…” Congress is responsible for authorizing military action; the president, as commander-in-chief, is responsible for executing it once authorized. In this case, Congress did not authorize the action in Venezuela and was only notified after it had already been taken. That inversion of roles is not a technicality; it’s the quiet normalization of unilateral war-making by the Executive Branch.

Trade agreements need the Senate and the House.

Rasmussen had Obama with a 62 percent approval rating in its last poll of his presidency. This particular pollster has never been accused of having Democratic sympathies.

Immigration occasionally made an appearance in the top three.

Georgia has a jungle primary approach to special elections.

LaMalfa passed away on January 6. Newsom has two weeks to call the special election.

Rep. Sylvester Turner (D-TX) passed away suddenly on March 5, 2025. Abbott scheduled the special election on November 4. Abbott scheduled the runoff for January 31, 2026. So, the district will have been without representation for almost 11 months by the time the runoff concludes. Newsom could pull a similar stunt, as a measure of payback.

Members get sick and have family emergencies. For example, Rep. Jim Baird (R-IN) is recovering from a car accident. It’s unclear how long he’ll miss votes. Rep. Greg Murphy (R-NC) is recovering from treatment for a benign tumor.

Reps. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA), Mike Lawler (R-NY), Rob Bresnahan (R-PA), and Ryan Mackensie (R-PA) signed the discharge petition before the House adjourned for the holiday break. Each of these members face competitive races in November.